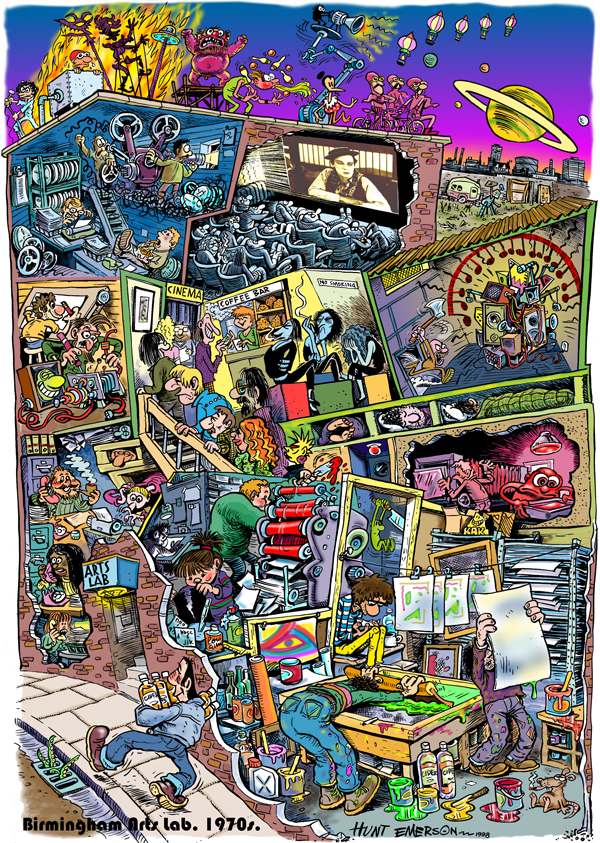

Back to the Lab: Hunt Emerson

Like most internationally renowned British cartoonists, Hunt Emerson lives in relative obscurity at his home in Handsworth. A Birmingham resident since he moved here as an art school dropout in 1971, he was a long time member of the Arts Lab Press while he honed his cartooning skills. What follows is edited down from a 90 minute conversation between Pete Ashton and Hunt: about his time working at The Arts Lab, what it was like, what, if anything, it meant, and how it affected his work and ideas.

Everything you might want to know about Hunt Emerson can be found at LargeCow.com. Hunt also co-runs Spritely Records in Handsworth. His latest book, an irreverent adaptation of Dante's Inferno, is on sale now and a retrospective iPad app of his comics was recently released.

Finding the Arts Lab

I came to Birmingham in 1971 to art college. I was there for a year before I fell out with the place and dropped out. I was a very young, young person. I was very stupid, I wasted my education. I mean. why the hell would you drop out of an art college? What I did know I wanted to do was get involved with avant-garde stuff. I read a bit about it and I was very interested in any kind of artistic stuff that was off the wall. I got to hear about this thing going on in Newtown, the Arts Lab.

They had a music workshop which I joined, which was basically a guy called Jolyon Laycock who’s still an avant-garde composer. His wife, me and two other people, we made a little group to perform his pieces, and they were really off the wall. Almost kind of theatre music, we did things like Anti-Symphony where we had a construction made of orange painted scaffolding poles with pieces of metal suspended in them and all contact miked-up and we’d be dashing out of painted doors in costume and whacking these pieces of metal and metal rods all through a big amplifier and a couple of big speakers. Unholy row. It was very complicated but it was weird stuff, funny and bizarre.

And that was where I was first involved there because I’d always been involved in music at home and I wanted to do some more of that, though I never really got into it in Birmingham though, until later. But I did find out more about the Arts Lab through that, the fact that there were painters and printers and that sort of thing.

At the same time I was doing all sorts of jobs. I worked as a library assistant, I was a postman, and I did clerical work in Winson Green Prison for a while. I was also learning about comics, which I didn’t really start doing until I left art college. So I was working during the day in order to spend the evenings becoming a comic artist. I realised that a way of joining together what I did for a living and what I wanted to do was through operating a printing machine.

First of all a friend told me there was a job going in the polytechnic operating a little desktop printing machine, basically a souped-up photocopier. I went and blagged my way into that job, saying I’d had some experience working at the Arts Lab on a printing machine, meanwhile I spent a few days nipping down to the Arts Lab in the evening and I’d stand by Ernie Hudson who was operating this printing machine and I picked up a few ideas about it and blagged my way into this job at the poly as a printer. Shortly after that Ernie moved his job to be a silkscreen printer so I came and took over his job at the Arts Lab first of all running the press, this A4 printing press. Quite quickly we got a bigger press, an A3 press, and we got somebody who was better able to run it, a friend of mine who was a motorbike mechanic. And I moved over to doing design work and dark room work, that sort of thing, preparation for the press, and I worked there for six or seven years after that.

The Arts Lab Press

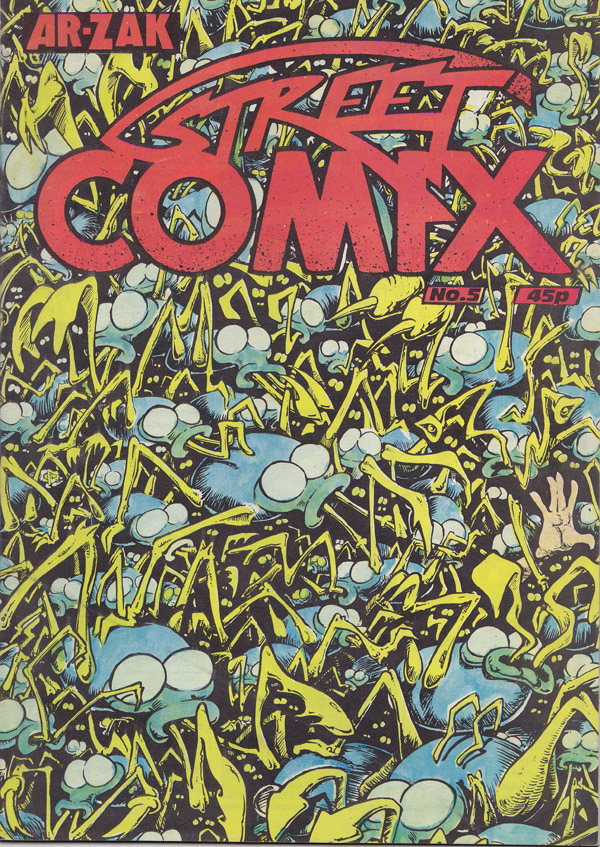

The press was there to produce notes for the cinema and the theatre and to produce the Arts Lab’s programme and to produce posters, that sort of thing. But we hijacked it to print comics, first of all my own things and then we started doing anthologies of comics and formed what we called the Arts Lab Press. Street Comics was our main title but we did some other titles as well, which were anthologies of some British underground comics of the time, or alternative comics as we liked to call them.

We were publishing quite a few people from Birmingham but we didn’t say no to others as well. Steve Bell was one of the early ones, we published his first comics and he went on to work for Grapevine first and then Broadside, or was it the other way round? Which were more like Birmingham political magazines, much more his scene, but we published his first comics when he was still a teacher. Bryan Talbot we published a bit of, Graham Manley and various others.

We were supposed to run the Press as a business but we never made any money. I had no idea about how the whole thing was funded, there used to be regular meetings, you know, committee meetings basically, discussing the finances and things but I haven’t got a clue what they talked about. I couldn’t understand why they wouldn’t just give us the money to do the comics.

But we kind of slipped under the radar with the comics. We managed to publish them kind of despite everything really until they stopped us doing it. We used up a lot of money that we shouldn’t have done really. But the smaller areas like poetry did get funded. There was money there in those days in the Arts Council so the poetry part of the Arts Lab would get money to put on four gigs a year or something like that and to publish a bit. And we being the Arts Lab Press found ourselves publishing a poetry magazine as well as the comics, which I hated.

I’m not a poetry person at all but we kind of had to do this, partly because it was part of remit but also because the guy running the poetry magazine was also a dope dealer so we wanted to keep in with him. But ah God when you get poets turning up who, because you’re printing their magazine, they believe you’re actually interested in their stuff so they turn up and want to read you all their poetry.

Mind you we used to get the same thing with cartoonists who would turn up on the doorstep with great bulging folders of work and expect to be made famous. We’d have to say “Very nice but we’re not interested, go away.”

It was very fertile, the whole thing was really lively. I look back at the comics now and I think they're not very good. They're of historical interest and people do collect them, though they're not worth a lot of money. But the actual things themselves, they're alright. There was some interesting stuff in there but they were just as amateur or as patchy as any other work like that. It's always the case that 70-80% is crap.

Seeing your work in print, and beyond that having the chance to experiment with that print, to all of us and the artists we were working with, everybody found it stimulating. People would push the boundaries because they had the opportunity to do so. We would encourage them and they would push themselves a bit more than usual to produce experimental work. Some of it worked and some of it didn't. We were printing from photographic negatives on to metal plates, and we used to work on the negatives, scratching out and painting black paint on them, creating stuff on the negatives that never existed on the paper. We'd be getting effects in the drawings, collaging things with feathers and bits of rubbish, stick them under the camera and see how that worked.

Publishing

In those days you couldn’t do self-publishing, you couldn’t do an edition of 30 of a magazine because the technology wasn’t there. To get something done you had to go to a commercial printer which meant you had to do X thousand of things in order to be commercially viable. Turn the machine on and you’ve got 500, you can’t just do thirty. So something like Oz and IT, the underground magazines, they were part of the magazine industry because they were printing 10,000 of these things which had to be sold and distributed.

We were kind of involved in the same thing in that we had the means of production and however amateur we were, we were kind of a step between commercial printing and self-publishing, where the artists got hold of the machinery, even though we weren’t competent to run this machinery, and produce 9,000 of a comic or whatever it was.

One problem was because we were artists ourselves, because we were part of the creation of it, people sort of felt they could argue with us about things. We’d find ourselves arguing about why a page looked the way it did. “Why couldn’t you do this?” “Because we can’t. It doesn't work like that.” “Well why not? You can get it done like that here.” “Ok then take it there and get it done there, but we don’t do this.”

But on the other hand we were also always interested in stretching things as far as we could and doing things with the printing machines which were way beyond their capabilities. The engineers would come round every three months to service the machines and they were always amazed at what we were producing. “What you did this on a Rotaprint 3090? That’s amazing! You’re not supposed to be able to do that.” But of course we wasted a lot of paper while we were doing it, and a lot of ink and things. We were playing around and experimenting.

We always felt as though the machinery was part of the process for us, that when we were planning a comic as an editorial team we’d be planning it right from the initial concept, who we might want to include in it, right through the costing and how we were going to produce it, who was going to store the things and who was going to actually put all the pages together. If you’ve got a 48 page comic book it means you’ve got to have a long table with piles of paper and people walking round them picking up paper all night. So we had to arrange how to pay people, cash, and then to make sure they actually did it and didn’t just get drunk. Arguing with your friends because you were expecting them to work and they didn’t see why you should be telling them what to do even though you were paying them for it.

We never had proper machinery. Everything was cobbled together. The printing press was a proper printing press but we had to produce A3 sized negatives and to make these we had an old photographic enlarger, a big wooden thing with bellows that stood upright about 7 or 8 ft tall, laid on its back, and you taped you artwork to the wall with arc lamps onto it.

In the back end of this enlarger we would put the sheet of negative and a wooden frame to hold it in place. And then we would focus it with the enlarger wheels, all in the dark or under red light, and photograph the things that way. When you think of the way things operate digitally these days it's just so primitive. It was never state of the art, never even approaching state of the art, but we used to get stuff out of it.

Had we ever been required for some reason to use proper professional equipment we wouldn't have been able to cope because we didn't know how it worked. We would have loved a proper process camera but we just never had one.

Who was the Arts Lab Press?

There was me. There was my friend Dave Hatton, who was operating the machinery. Before him there was a guy called Martin Reading who was a very dynamic guy and he operated the press but he also did a lot of other things as well and eventually went off to form a commune in Wales. There was originally a guy called Paul Fisher who was a writer and performer and he used to help us do editorial stuff. There was another cartoonist called Chris Welch who had been one of the Nasty Tales and Cosmic Comix crew who came to live in Birmingham for a while. Suzy Varty worked with the press doing basically the job I did after I left although we worked alongside each other a lot. And one or two others came and went as assistants working in the darkroom. Chris, Suzy and I were the only cartoonists involved but there was a group who were interested in what was going on in the Press. And they came from various creative disciplines. Martin Reading originally had been involved in theatre I think, and he was very much involved with the communes movement and magazines that they produced. David Hatton is a motorbike fan and just liked printing. It was just a little group.

Organising Spirit

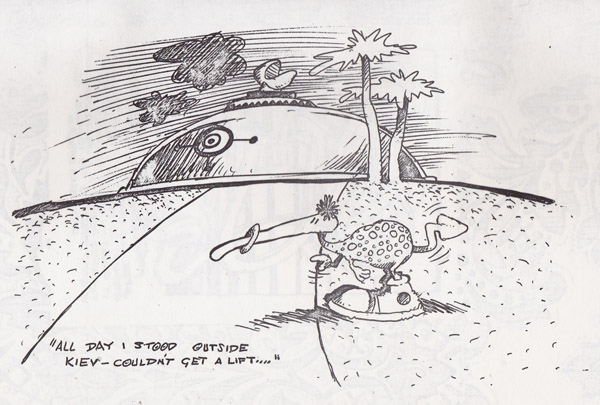

I don't know whether it's because of working at the Arts Lab or whether I'm inclined that way anyway but I'm an organiser. And maybe it's because my experience at the Lab was always like that. People would suggest something and you would get involved and find yourself knocking together a film set out of rubbish, scouring the streets looking for junk for what was supposed to be a wrecked spaceship for somebody to make a bit of film of. And I would find I'd spent four days doing that, because it was fun! Because somebody had to do it! Most people would say "oh, well, I don't know about that" whereas I'm just prepared to roll my sleeves up and get stuck in.

Working at the Arts Lab, there was always something going on. Sometimes I was not involved or I was antagonistic towards what what was going on and sometimes I wasn't, but there was always something. Sometimes it would be great and sometimes it would be rows all the time, mainly because of money.

Inside Tower Street

At Tower St we were in a building which was originally a gym. There were two big studios at the back which had gymnasium wall bars like you had at school. There was a big room upstairs which became the cinema and the ones downstairs tended to be used for dance and theatre. The front of the building was small offices where admin went on and where we had the printing presses. There was a coffee bar upstairs.

In was a right warren of a place. Where we had the darkrooms was what had been the showers, so it was all that kind of granite aggregate stone, and that was where we had the darkroom because it had water and there weren't any windows so it was easily blacked out. There was an enlarger in a toilet cubicle.

There was about 4ft of space between the floors and people used to live in there. Visiting theatre companies or dance troupes, if they needed to be put up overnight, there'd be beds down there. There was a trapdoor under the coffee bar. You'd have an afternoon showing of something with people queuing for tickets and then the trapdoor would open and people would climb out.

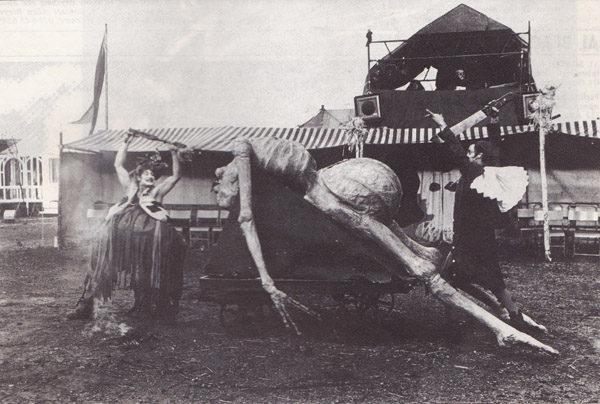

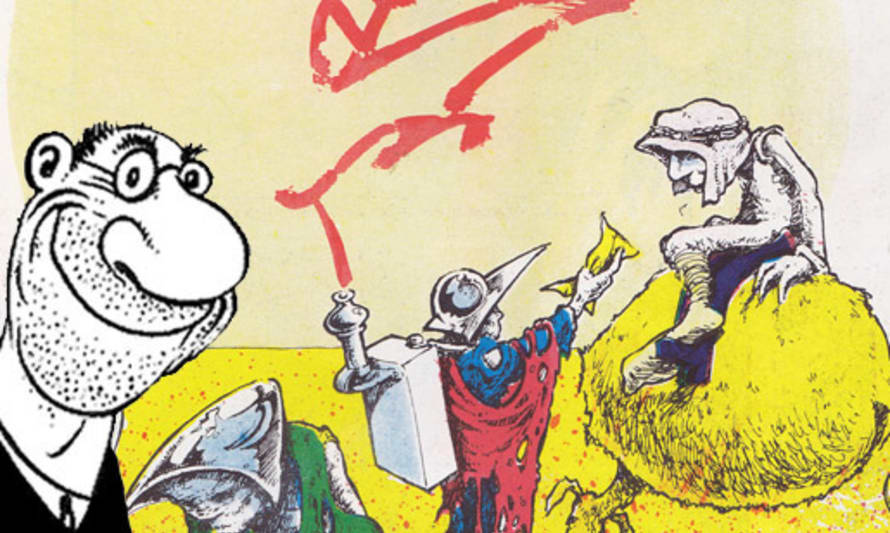

It was a very eccentric place. We used to get strange theatre groups. The People Show was one, and Welfare State (pictured). This was avant garde performance art rather than theatre. Welfare State, for example, when they were building what is now the old library, when it was new library, Welfare State built a tower of about 10 cars on that building site.

There was a bunch called John Bull Printing Outfit from Hull, and they used to do a thing called the Cyclamen Cyclists - they all had bicycles and Victorian skin-tight cycling costumes all in purple with leather helmets and goggles. You'd be on a train pulling into a station and they'd be standing there with their bikes in formation. Or they'd come wheeling round the top of New St in formation. They did an ascent of New St once where they were all kitted out and lashed together like mountaineers and they climbed up New St.

There was a regular audience and it was reasonable. These things did get a reputation and people would come and see them. They would be able to just gauge exactly how long to have them there before the audience started disappearing, so any of the 500-odd people in Birmingham that might want to see it would get a chance. But with the avant garde music workshop that I was part of, we used to play to 3 or 4 people. The layabouts who used to hang around the Arts Lab Press, our mates, they would come in with their cider and watch it, then you'd get the art critic from the Post and Mail and other avant garde musicians, and that was it, that was all that would see it. I'm probably exaggerating the lack of audience a bit here, but that's how it felt!

Moving to Gosta Green

Gosta Green was an entirely different thing. We knew that we had to move the Arts Lab for years and there was all sorts of possibilities with Birmingham being redeveloped. There were various places we could have gone to and nobody could agree. We might have wound up in Brindley Place, where the Ikon is now. And the least favourite option was Gosta Green, and of course nobody could make their mind up until there were no options left.

And we knew, some of us, that moving to Gosta Green was a step on the way to becoming the University's art cinema, which was basically what happened. Gosta Green was cleaner and more organised and corporate. More really the way it should have been. It's just a shame I didn't like it there. But it was inevitable that it went in that direction. Tower street had run its time. It went on for a long time, considering everything, but the anarchic, haphazard nature of it couldn't be sustained. It had to become more organised, and of course the Lab at Gosta Green hosted and promoted some fantastic shows and wonderful, inventive programming that would probably have been impossible in Newtown.

Thanks to Hunt Emerson for his generous time. Please buy all his books. More info on FLatpack's Arts Lab events can be found here. The 1998 Lab cartoon pictured at the top will be available as a signed, limited edition A3 print at the Flatpack Palais over the festival's final weekend.