Back to the Lab: Pete Walsh

In 2009 I recorded a chat with Pete Walsh in the bar at the Irish Film Institute in Dublin. Pete had landed a great job there in the mid-80s after 25 years of film programming at the Birmingham Arts Lab and then the Triangle, and most of our conversation concerned this earlier period. The intention was to post this online at the time of our Lab tribute during Flatpack back in March, but thanks to festival frenzy this never happened. It's a year today since Pete died, and high time we rectified this.

The memories below were culled from a good 90 minutes of chat. As always Pete was very generous with his time and spoke fondly of his Birmingham years; though as you'll see, there were regrets too. (For another perspective on the Lab saga, see Pete Ashton's chat with Hunt Emerson.)

Early days

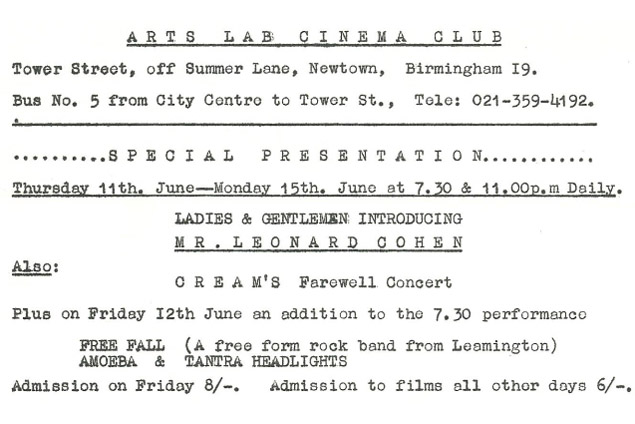

I arrived on the scene as a student, after having shown Andy Warhol films at college, and they invited me to join them basically because they saw film as part of a programme they could put on in these premises. Despite the fact that these premises were tiny, they were out of the way, back-street, all the rest.

The Lab people were involved in things like music promotions – music had a lot to do with it. There was a visual arts element, represented by Simon [Chapman] who went on to work at the Ikon Gallery, and there was Peter Stark who was an academic who was interested in the sociology of the arts, and in what young people were doing in the arts, which seemed to be something different to what people had done before.

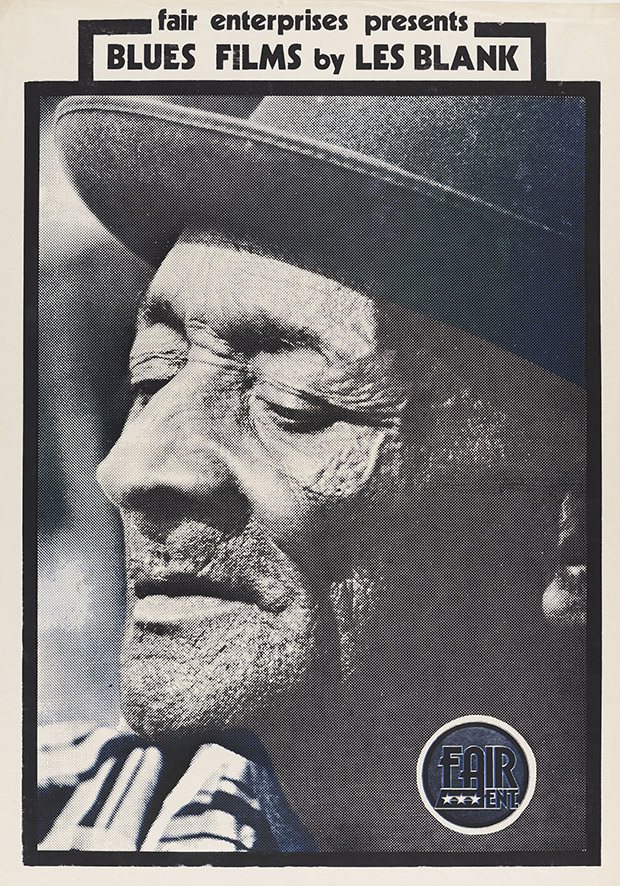

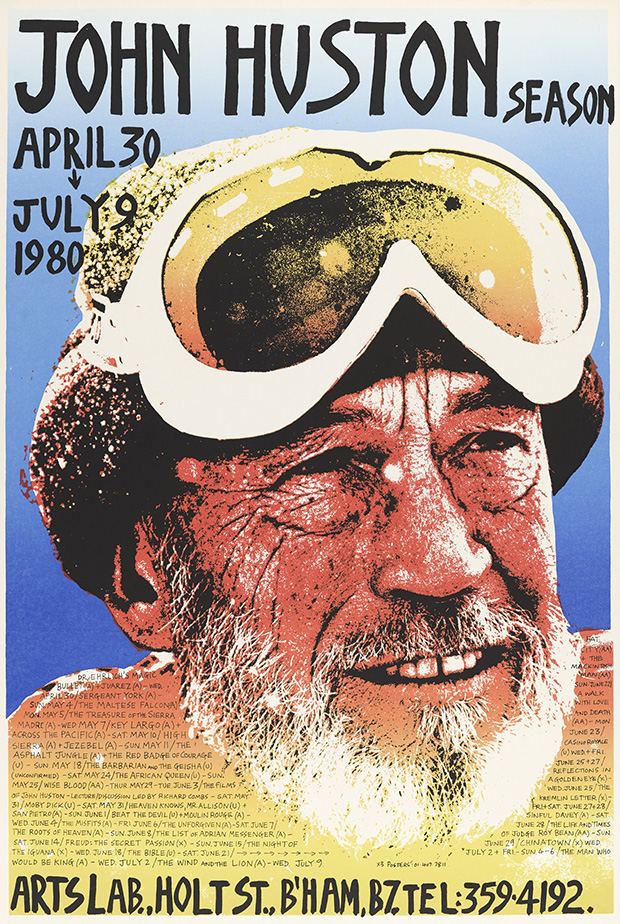

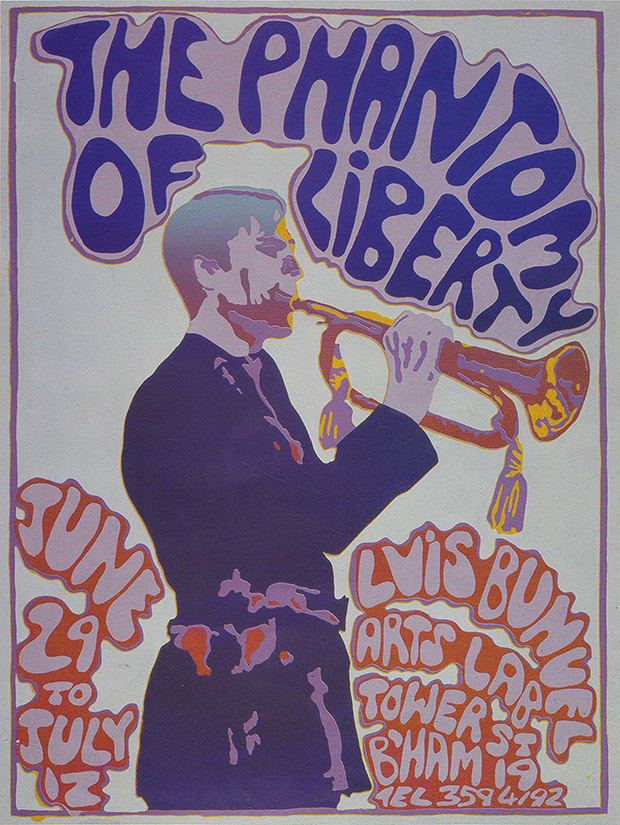

Design was part of it, through Bob [Linney] and Ken [Meharg] mainly. They were university science students, and they liked the place so they decided to set up their own silk-screen printing press there. And it was the kind of place you could, as opposed to the Midlands Arts Centre. A lot of people saw it as a reaction against the Midlands Arts Centre, and there was some truth in that.

It was a kind of collective, it wasn’t a commune; although people did sleep on the premises. The owners of the building, the Birmingham Settlement, sort of turned a blind eye to that. I mean, Bob and Ken and Tony [Jones, who set up the cinema], and Simon, all literally lived in the building at one time. I remember, with some amusement, that the sleeping quarters were above and below the coffee bar, and given the sort of lifestyle these guys were leading you would end up with punters coming in and a door or window opening above the serving area, and somebody just getting out of bed. Which must have been an odd sight. The whole building was kind of ramshackle, and the cinema was self-made, self-constructed.

So you only attracted a certain crowd who accepted that sort of setting I suppose – it’s going to turn off a certain number of people.

…That’s right to an extent, but because of the kinds of films we were showing – and which nobody else was showing in Birmingham – it was quite astonishing the range of audiences we got. You know, middle-class people who were interested in art cinema actually braved and enjoyed it, or at least that’s the impresson we got.

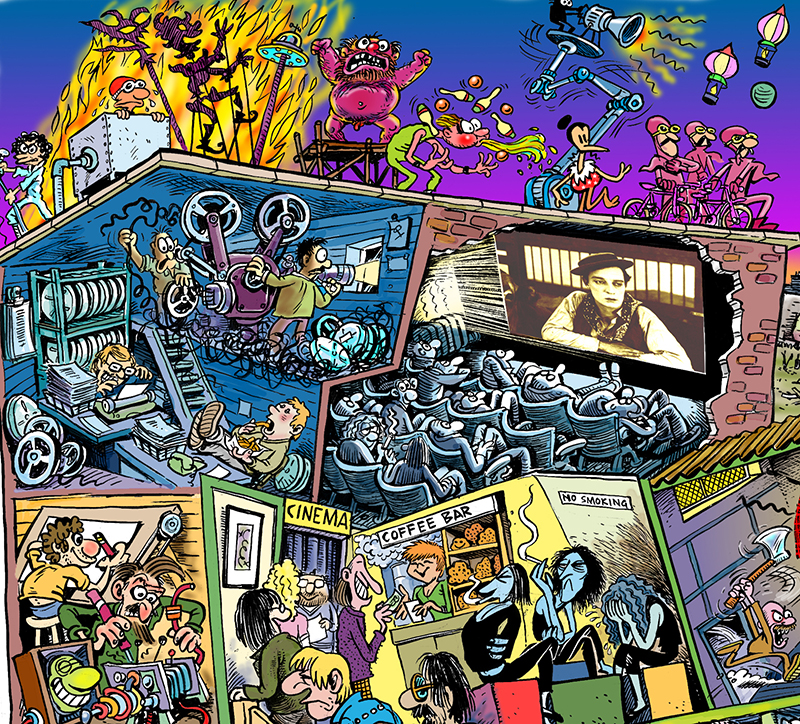

Detail from Hunt Emerson's 1998 cross-section of the Lab. Pete is the one eating chips.

Detail from Hunt Emerson's 1998 cross-section of the Lab. Pete is the one eating chips.

Going legit Peter Stark was the person who tried to impose some sort of structure on this ramshackle bunch, because we were fairly anarchic. He was the first Director I think, and I remember hilarious meetings… his attempt to impose some sort of order on the running of the organisation, with certain prescribed roles and responsibilities. I don’t think responsibility was something that many people were very keen on – it was something that they were trying to escape from probably.

The collaboration between Bob and Ken on the posters and Tony and myself who ran the cinema, was done on a very pragmatic basis – we liked their work, so we would ask them to do posters. They were interested in film, they would go and see a lot of the films we were showing. But then eventually a structure emerged, whereby a programme was produced, was advertised, staff were needed to ensure that the events happened when they were supposed to happen, and it was gradually professionalised. But still there was a dire lack of money, and people. I remember, when I was a student – it must have been about 18 months or 2 years – I received no money from the Arts Lab, even though I probably spent more time there than I did on my course.

So did you have to get a day-job when you left education?

There was some kind of tiny wage, I do remember teaching at Birmingham Poly, and I did some extramural teaching for Richard Dyer who was at Birmingham University then - and I know well that I earnt a lot more money from a half-day teaching than I did the entire week working at the Arts Lab. It was kind of essential for survival. But it did improve gradually, and the programme became quite ambitious and intense and there was money to put that programme on.

We showed a lot of avant-garde films in the early stages, not just Warhol but the whole gamut of them… Then that gradually became replaced by auteur cinema and more mainstream cinema. That was the time of Movie magazine, and Robin Wood writing those wonderful books on Hitchcock and Hawks – which were key influences on me, I must say. So we started to structure the programme in a way that was very auteurist.

There was a lot of New German Cinema…

…Yes, and whatever was current, and seemed to be most interesting at the time. We went to festivals... Edinburgh was our first big adventure, actually. I remember Tony used to drive us up there in a van, and it was only later we realised he didn’t even have a license at the time. This is when Edinburgh were doing retrospectives as well, they did the famous Corman one, and Sam Fuller and so on. It was the time that Lynda Myles was Director, and we’d go there religiously every year, and pick up ideas for our own programme.

But in Birmingham did you feel like you were in a little oasis of your own – there wasn’t a film culture to speak of?

No it was very small-scale. There were other cinemas in Birmingham that you might describe as art cinemas, the Jacey and the Cinephone, and there was that peculiar mix which goes way back to the 50s when continental cinema was associated with soft porn – so that a cinema like the Cinephone would be showing a European sex-movie one week, and a Godard the next. It was kind of weird.

Growing pains

Anyway, the programme gradually became more ambitious. I steered it more in the direction of supporting it with a publication, and that grew and grew almost to the point of becoming a magazine. By that time Tony was about to move, and the Arts Lab itself became more sectional – there was the cinema, and there was a theatre programme, and there were exhibitions, and the music group, Jolyon Laycock and other people. And there was often antagonism actually.

Part of it was simply because we were all using the same space, so that if there was a theatre production on I couldn’t show films which would piss me off, and the same when it was music. In fairness to the people who were involved with theatre and music, and this particularly applies to music, their whole ethos was towards the avant garde and experimentation. They never dabbled with the mainstream to the extent that we ended up doing with cinema.

I think it’s probably fair to say that Tony and myself – well, it certainly applies to me – we became sort of cocooned in our own little world of cinema… so, this notion of creative collaboration, it didn't really happen that much. We were doing quite different things and in the end of course, not just through economics but the way things go and the way organisations develop, it was bound to to splinter. And it became a problem for the funding bodies, as it always does, because there’s not much money to go around.

So is that the main reason why film ended up swallowing up the rest of the programme, because it was cheaper to run? Not because you and Tony were better at politics?

Absolutely. In fact we were hopeless at politics. It was simply expediency on the part of the organisation – the cinema attracted more people, and it was cheaper to do. You can’t keep putting theatre productions on all the time, because it’s incredibly expensive. Yes, it’s as simple as that.

So there was some resentment from the other artforms?

It did build up, yeah. And of course it would over time, because how long are we talking about, quite a lot of time actually…

Twelve years or so?

A lot of things happen to organisations and people over a decade. It was no surprise really. And then the premises at Tower St were never adequate for the organisation to be a serious venue, it was a kind of joke really, an Off-Off-Off-Broadway outfit that only the people who were really dedicated or intrigued enough would actually brave it. It was never going to last forever. And then the deal came with Aston University.

Moving to Gosta Green

So a deal was done, and that was a big issue for the fiercely independent bunch of us at the Arts Lab – the idea of going to premises on Aston University was complete anathema, you know, it was seen as some kind of ultimate sell-out.

The Centre for the Arts’ programme was quite mainstream compared to the what the Lab was doing…

It was, it was pretty straight-laced, and the whole thing was a bit of an anomaly. Aston was a technological university, so the idea of putting arts events on for that bunch of ‘spanner-men’ - as we used to refer to them - was vaguely ridiculous. The Arts Lab by comparison had a much more public audience, so it was inevitable that people thought if you combine these two maybe you’ll get something that works, and it’ll cost less money. I think it was as pragmatic as that, and that worked for a while… However, we went there on the basis that the Arts Lab would remain completely independent, and we had our own space. And of course that was never going to work, it never does. And some bureaucrat thought, ‘the next phase is obvious: we just have one organisation, we’ll save even more money.’ And that was seen as even more of a betrayal.

So this unholy new creature was born, called the Triangle. It was supposedly a merger between the Arts Lab and the University Centre for the Arts, but the crucial thing was it gave Aston University control and the Arts Lab’s independence was completely gone. We were all employees of Aston University basically, and they were pulling the strings. There was still money from West Midlands Arts, but I think West Midlands Arts were probably a bit unhappy with the whole arrangement anyway, particularly when activities other than cinema began to be whittled away. And then I think West Midlands Arts actually withdrew, leaving just the University. That was awful actually, they should never have done that, there was no real justification for it, because the amount of money was so small. The likelihood was that Aston would lose patience, and lose interest, even in just a cinema-only operation. Which of course duly happened. And we know the rest.

It’s kind of miraculous that it survived as long as it did, isn’t it?

It is actually. But it’s a pity for Birmingham, though, that nothing good came out of it. The work that we did, back in the 70s, you would’ve thought it would lead to something on a much bigger scale than you’ve got now. Some kind of establishment even. Like you do have in other cities, like Filmhouse in Edinburgh, or Cornerhouse in Manchester.