The Occupation, Fifty Years On

Our new marketing assistant Keenia Dyer-Williams is a recent University of Birmingham graduate. Fifty years to the day since a major protest saw over a thousand students occupy the Great Hall, she reflects on the legacy of that protest.

1968 was a politically turbulent time, no matter where you seemed to be in the world. In the US, the Nixon/Humphrey presidential election had proved to be one of the most chaotic in history, while student protests had been spreading across European cities and US campuses since 1964. Contrary to what some may believe, Birmingham wasn’t living in its own bubble, sheltered away from the politically active climate of the time. The University of Birmingham saw direct action take over the campus towards the end of the year, with students occupying the Great Hall, offices in the Aston Webb building, and even the Vice-Chancellor’s office. Fifty years on, we’re looking back at what sparked this activist spirit in the students of ‘68, and how things compare today.

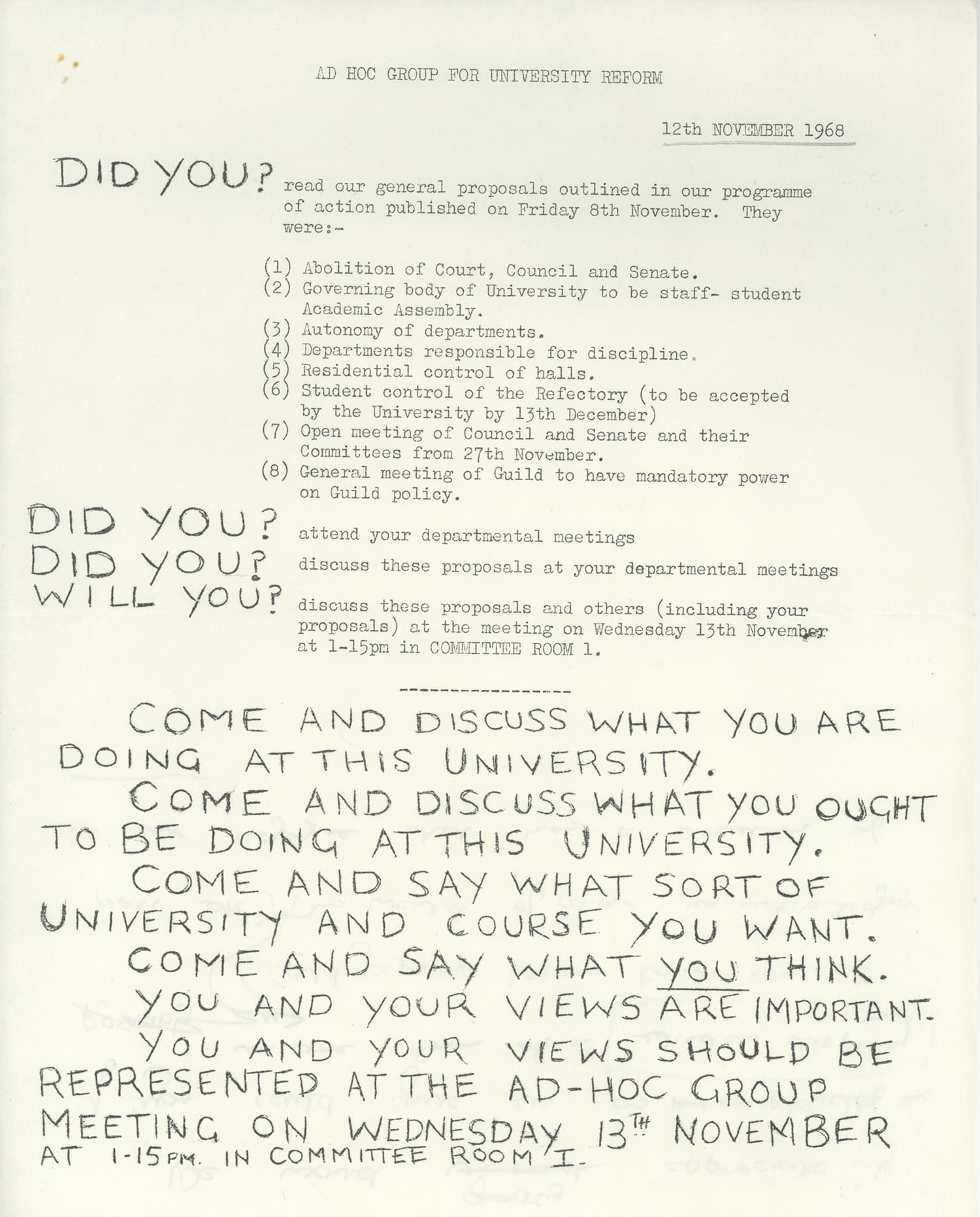

The Guild published ‘The Student Role’ in February 1968. It was a seminal report calling for greater student representation on the University Council, Senate, and departmental committees, thus ending what many were deeming the ‘second-class citizenship of students’. For months, this report was discussed by the Council, but they were discussions students were excluded from.

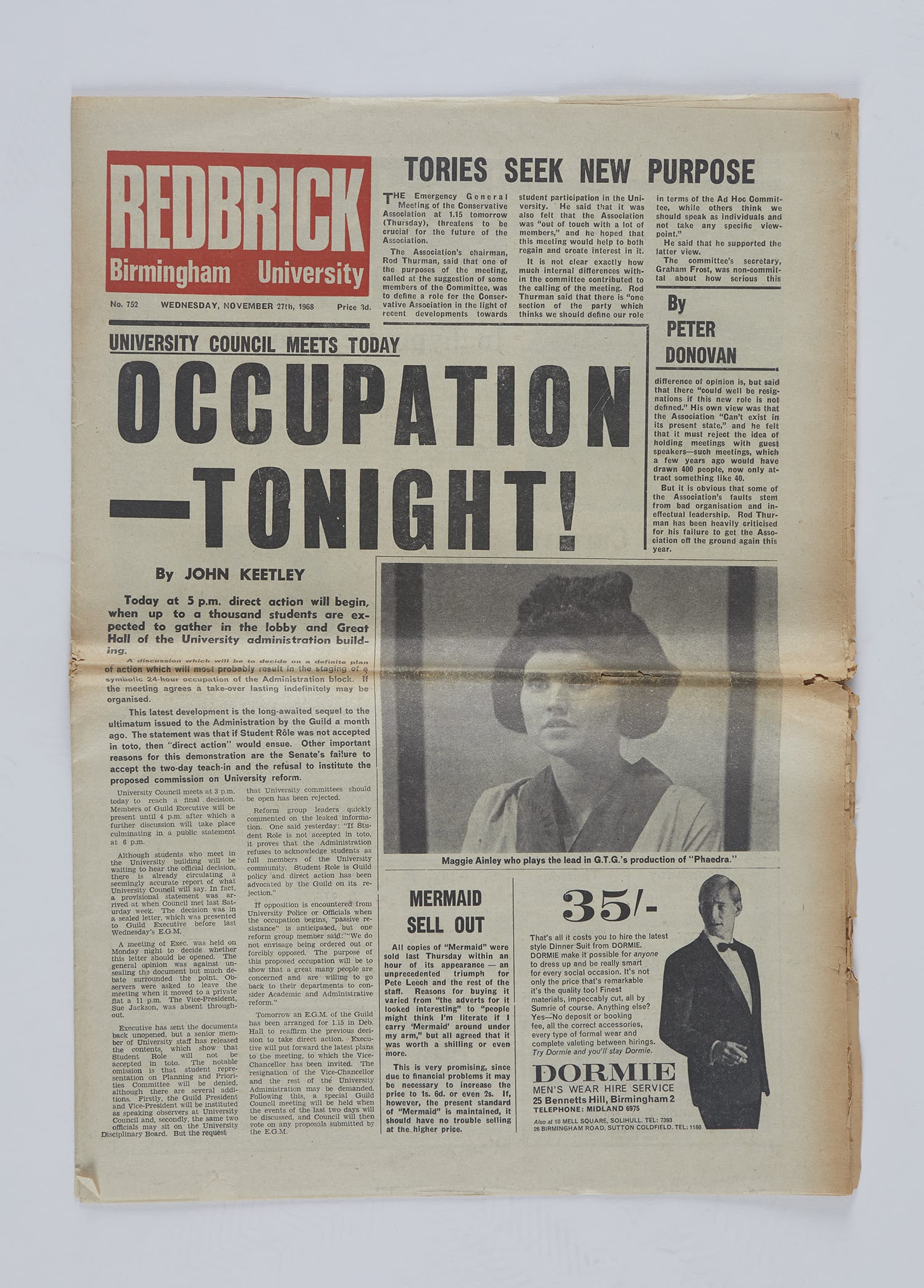

Students, and some staff including sociology postgrad Dick Atkinson, started coming together regardless of differing political opinion in an effort to make fundamental changes to the university’s undemocratic governmental structure. This outdated system had not been changed from the previous century, where there were no students on either the Court, Council or Senate. Allowing students access to these top committees would’ve also helped to do away with the university’s obsessive secrecy and regularly closed off meetings. Discussion groups often came together to discuss this, as well as the role of student and teacher, teaching methods, examinations and assessments, university entry, and much more. Just a quick look at several Redbrick papers from 1968 gives a taste of how students maintained an active dialogue, either by sending in satirical illustrations and propaganda, replying to each other through letters, or giving updates in news articles.

Although movements were beginning to be made in some departments as they developed small student committees, some saw this as a tokenistic gesture that wouldn’t bring about real change. Though not everyone could agree on how militant their approach should be, it seems that most students in support of ‘The Student Role’ agreed it was time for them to be recognised as adults, capable of making decisions for themselves. After months of meetings and toing and froing, negotiations continued to break down and tensions came to a head. Students finally had the impetus they needed to take things further and properly organise a way to voice their frustration.

Direct action and a protest demonstration were arranged for 27th November, as an ultimatum to the university if they didn’t accept the report in its entirety and allow open access to Council, Senate and committee meetings. But before November had even arrived, the university already rejected what many felt were the most important parts of the report. Rather than bring the whole university teaching staff to a standstill, the Guild decided to stage a sit-in to target senior officers. It was Guild Secretary Chris Tyrell who proposed that the sit-in take place in the Great Hall and Vice Chancellor’s office. A small group called Ad Hoc, which was separate from the Guild Council, had a more radical approach and were keen to move things on quickly. They were the first to occupy the Great Hall, before finally moving on to the Vice Chancellor Hunter’s office where they gained access through an open window. A bigger influx of Guild members and other students followed not long after, and over 1000 students initially occupied the Aston Webb buildings. However, the Great Hall formed the central hub during the occupation. Not only was it where people slept, ate, held meetings, and produced posters, but it holds major significance as a building being one of the university’s oldest (alongside Old Joe) and the location for degree ceremonies.

The political atmosphere was kept alive throughout the sit-in by continuous debate, propaganda and monster rallies. There was an effort to keep the building full of occupiers to avoid a potential ‘countermove or lock-out of some kind’, according to former Guild President Ray Phillips. Jenny Wickham, News Editor of Redbrick in 1968, describes how members of the Conservative society took part in the sit-in: ‘A lot of people took part because they thought it was right more than because they had made a political [objective].'

Some students didn’t even know the background of ‘The Student Role’, having only been at university for a few weeks, yet still found themselves caught up in the protest. Despite so many people of different backgrounds and opinions occupying such a space together, the students managed to maintain relative peace and order, with the biggest squabbles being what time to turn the music off to keep both early sleepers and late-night partiers satisfied. There was a sense of real organisation and effort being put into doing things properly. From the way students interacted with each other to leaving the spaces they occupied how they found them, they did everything to ensure nothing discredited the demonstrations.

Not everyone was in support of the student demonstrations. There seemed to be a generation gap, particularly with older people in the local community dismissing it as a ridiculous ‘display’ of students making a fuss over nothing. Even former Vice-Chancellor Sir Robert Aitken stated he’d felt most students had exploited their new-found power like ‘heady wine’, and that demonstrations like this would always be bad news. Watching the archival news clips, it’s hard not to notice similar views about young people being echoed today, especially since Brexit. Nice to know that it’s not just millennials who’ve had that ‘over-entitled, over-sensitive snowflake’ insult thrown at them for caring about genuine issues!

Many other students and staff - particularly in Science and Engineering – also didn’t understand the ‘militant’ actions of their fellows. One person states in Redbrick that ‘“we are not here to run the place but to get a degree’”, typifying a lot of the views of students opposing the occupation. By 4th December, support for the occupation to continue was waning, and even those who agreed with ‘The Student Role’ urged for it to end.

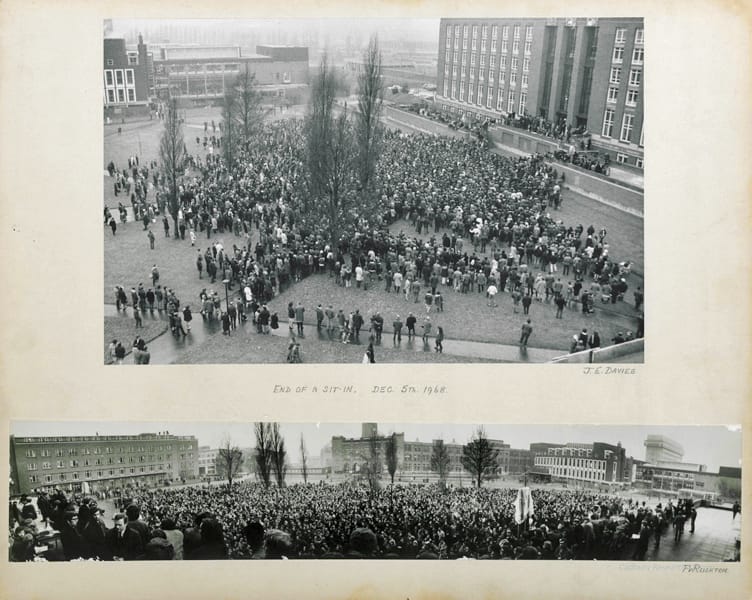

On 5th December, an open mass meeting was held in front of what used to be the Main Library to decide whether the occupation should carry on. Over two and a half thousand people turned up to participate, which constituted then to a third of the student population! The students were only willing to discontinue the occupation so long as the university agreed on the Four Principles: ‘no victimisation, all university committees to meet in public, the right of students to a say in university government and a commission to examine the role and structure of the University’. The majority of students voted to end the occupation, and a review followed leading to an agreement between the Guild and University for full student membership of a number of university committees.

As an alumnus of the university, I’ve seen first-hand just how active students are in debating, organising and managing the many things that happen on campus. This is why it’s pretty surprising even for me to learn how poor representation used to be. Students are absolutely essential to a university, so their views on how theirs is run should be taken as seriously as those at the top.

Yet fifty years on from the Occupation of the Great Hall, tensions have been rising in the community as students are once again calling into question the university’s willingness to put them first. This comes in the wake of one particular incident, where a man was repeatedly stabbed in an attempted carjacking on Heeley Road in early October. There has been a huge increase in crime in Selly Oak over recent years, particularly burglaries, muggings, sexual assault and rape. There was a violent or sexual assault for every day of the year in 2017, and it’s known that crime significantly increases during the autumn and winter months. You only have to scroll through the hashtag ‘#StaySafeSelly’ to understand the sheer amount of incidents and concerned students scared to leave their own homes.

The University’s response to this has been that the area ‘isn’t a crime hot spot’, implying a simple locking of doors and windows would solve the issue. Understandably, students are infuriated with this and have been discussing on social media whether a sit-in, or some other form of protest, may be the answer.

And it’s not just students who are unhappy. Teaching staff are complaining - and have been complaining for years - about the ‘Sports Direct’ payment structure that’s common among Redbrick universities. The University of Birmingham has the highest proportion of frontline workers on temporary or zero hour contracts, with over 70% of academics on insecure contracts. This information came out at a time when the university were just beginning their Green Heart project - the importance of which some have called into question when the majority of the working force operate as casual workers, and not enough is being invested in local student safety.

To top this off, Sir David Eastwood at Birmingham University remains the highest paid Vice-Chancellor in the country, with a reported salary of £439,000 - nearly double the average pay for a Vice-Chancellor in the UK. Some have disclosed that their colleagues don’t feel comfortable voicing their frustration for fear of reprisals, just as many students and staff were concerned about where censorship may lead them during the Occupation. However, more than 160 academics have signed an open letter of complaint. It calls for an enquiry into the Vice-Chancellor’s high pay, and reform of a system that offers disproportionate rewards for the few at the expense of the many.

Before the Birmingham ‘68 project, I had no idea that the University of Birmingham campus has witnessed so much student activism. Being a former student, it genuinely gives me pride to see students, past and present, making a stand and rallying together for a collective cause. To see history almost repeat itself like this leaves me with mixed emotions, though. Interestingly, even though there’s certainly a stronger student voice on campus, apparently ‘only two student seats on the body [appear] to be filled’ in the composition of the current University senate. Some have claimed this is due to today’s students’ indifference to university politics, but it’s unfair to paint all students with this brush. Of course, there will always be some students who just want to focus on their degree above anything else happening on campus, yet I see a similar spirit ignited in the majority of students today that I felt from looking through archival Redbrick newspapers from fifty years ago. Students have never stopped caring. Though a lot of the conversation may now be through online petitions and social media rather than letters and flyers, students are more connected than ever and using their collective voices to demand change.

Written in contribution to Birmingham 68; an ongoing research project into the culturally significant changes and events happening in the city around 1968. Supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund, "B68" has enlisted the help of a dedicated group of local historians to produce a series of blog posts, podcasts and contributions to a final publication due to be released in early 2019.