When Yoko Ono Came To Birmingham

In spirit and in distance, San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park is a long way away from Cannon Hill Park, Birmingham. The former brings to mind Summer of Love abandon and Haight Ashbury bohemia; the latter, Sunday picnics and swan boats. Yet, in 1967, both parks were witness to the type of event that would come to define popular ideas of sixties counterculture – the Be-in. Golden Gate’s is no doubt the better known: on 14th January Allen Ginsberg, The Grateful Dead, and tens of thousands of attendees got together for body painting, bubbles, psychedelic rock, and copious amounts of LSD. Roughly nine months later, though, on Sunday 15th October, Cannon Hill would see its own such gathering, albeit more restrained and in typically British weather. Leading this less documented Be-in was Yoko Ono.

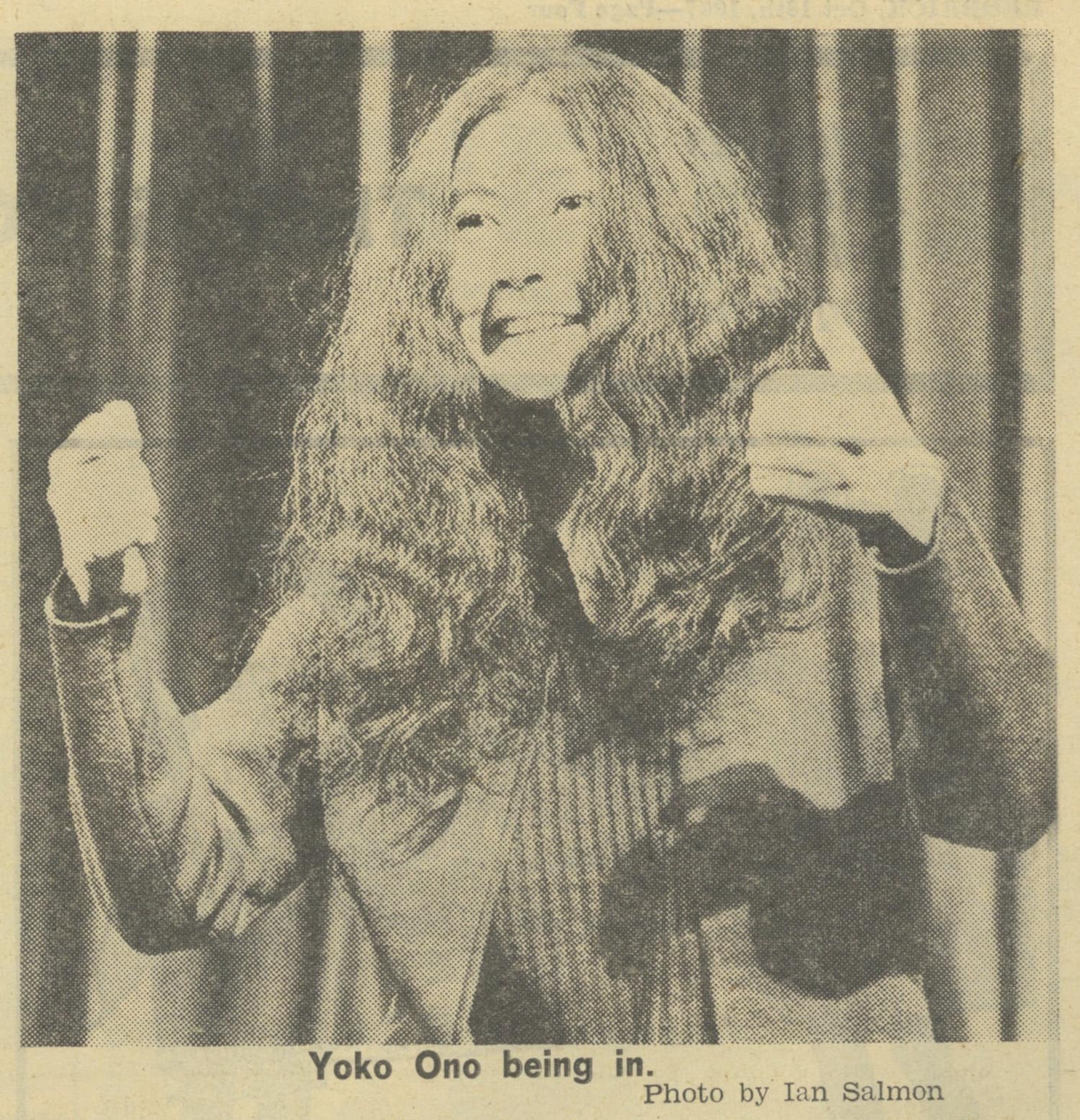

The above image, taken from a review of the event in University of Birmingham’s Redbrick magazine, is immediately recognizable as Yoko. With her scraggly dark hair and thumbs-up optimism, Yoko looks out at the crowd in the same way that she would look at reporters’ cameras for the rest of the sixties. As familiar as this image might be, though, the absence of John Lennon by her side is striking. In fact, the Beatle makes no appearance in this Redbrick account, which variously refers to Yoko as ‘Miss Ono’ and ‘a Japanese woman in her mid-twenties’. Though the two had met a year prior at a London art gallery, Yoko and John would not marry until early 1969. Here, then, is a rarity: a British press review of Yoko as an artist in her own right, rather than – as would soon be the case – the wife of a Beatle.

But what exactly did Yoko’s Birmingham Be-in entail? According to the Redbrick review, she began by listening to a ‘Perspex-cased clock […] with a stethoscope’, an activity that the audience, made up of ‘students with a smattering of adults and schoolchildren’, soon joined her in. Meanwhile ‘tubes of bubble mixture, pieces of coloured paper and cryptic messages saying “whisper” and “think” were passed around’, as Tony Cox, Yoko’s manager and then husband, tied ‘string first around the trees, and then around the fingers of individual members of the audience’. Then, after one woman – identified by another press report as 24 year old Tamara Brown – put ‘a curse on time’ by smashing a watch, and a group of dogs interrupted the solemnity, it started to rain, forcing everybody into the Midlands Art Centre.

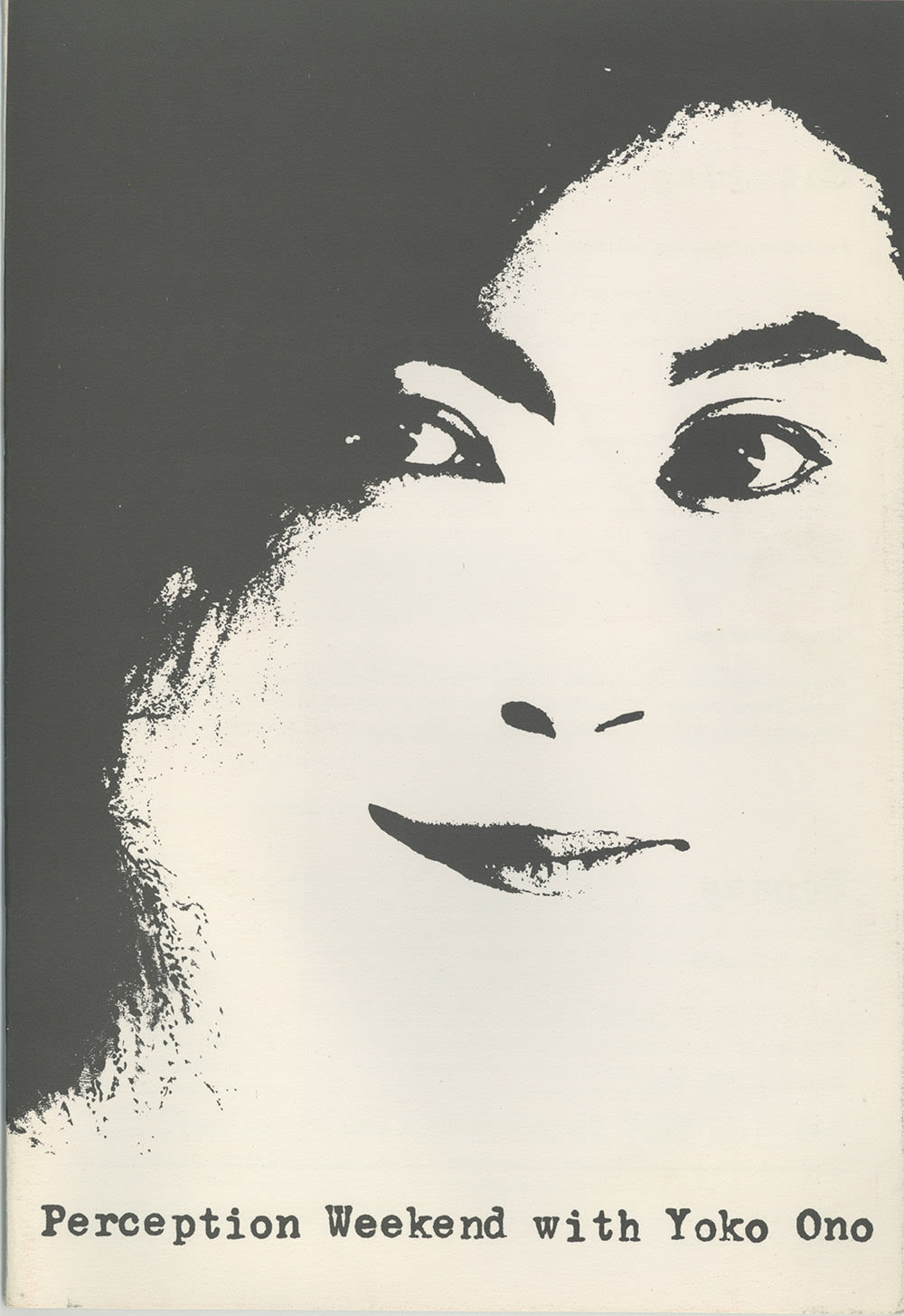

This Be-in was in fact one small part of a larger ‘Perception Weekend’ – an Arts Council funded event that, in the December of that same year, would include Pop Art pioneers Richard Hamilton and Peter Blake. On the Saturday, Yoko screened her notorious ‘Film Number Four’, a compilation of people’s bare bottoms, and her Cannon Hill appearance is indeed indicative of her broader artistic endeavours in the mid to late 1960s. Those ‘whisper’ and ‘think’ cards bring to mind her 1964 book Grapefruit, a book of her famous instructional pieces. With these Yoko directed her audience to create art works, some more conceptual than others: ‘EARTH PIECE’ simply reads ‘Listen to sound of the earth turning’. In their Zen directness, ‘whisper’ and ‘think’ also anticipate Lennon’s ‘Imagine’.

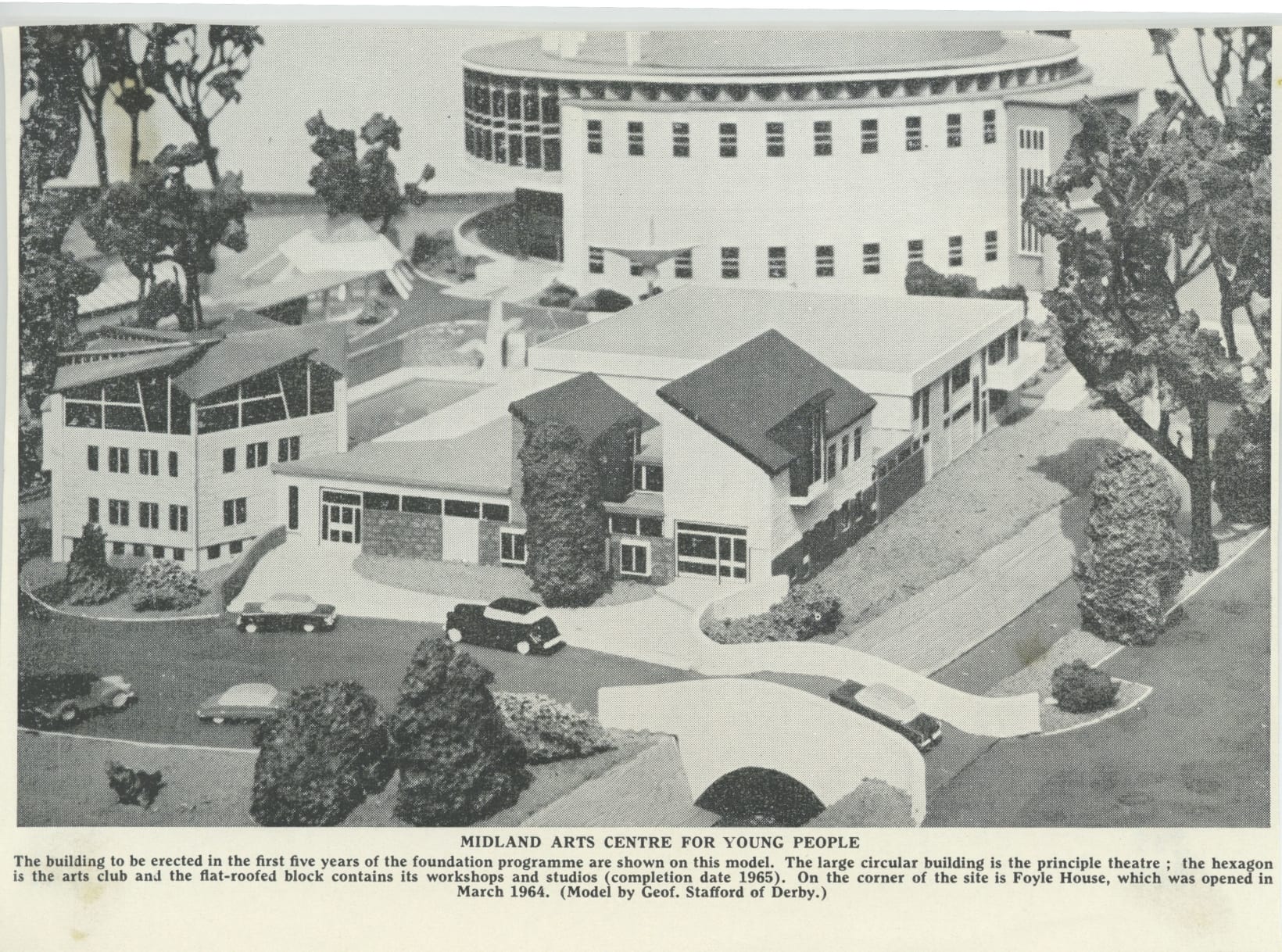

It is tempting to see Ono’s brief appearance in Birmingham as a small drop of avant-garde wonder in a city otherwise lacking in the kind of energies that, for a few years at least, made London the capital of the art world. The Redbrick review ends pessimistically, noting how ‘one was left with the impression that like the bubbles that people were blowing, the fruits of the Be-In were very, very transient’. It’s true that - to our knowledge - Yoko has never returned to Birmingham, although she has visited Coventry at least twice. The dearth of material documenting this Be-in would also suggest that it amounted to little more than a colourful reprieve from a dull autumn afternoon. And yet, it was not out of keeping with some of the other experimentation going on at MAC around that time.

The MAC was established in 1962, by the ex-chemist and theatre evangelist John English, and with the support of the councillor responsible for much of Birmingham’s redevelopment in the ’60s, Sir Frank Price. By 1968, it had become a hotbed for creative Brummies: the proto-prog band Bachdenckel recorded their first tracks there, and other members included underground cartoonist Edward Barker and the actor Tony Robinson. In 1969, though, some started to grumble at the more daring activities taking place at the MAC. In particular, visiting theatre groups from Switzerland, Germany and Poland, whose performances involved naked sexual thrashing and hard-to-remove red paint, led city councillor Nora Hinks to call for the centre to be closed – in her words, Birmingham was ‘becoming a decadent city… a sink of iniquity’.

For a decade that moved as quickly as the 1960s did, it is fitting that Yoko’s affirmative and good spirited ’67 appearance had given way, by ’69, to controversy and clampdown. Cannon Hill Park does not normally figure into narratives of this crucial period, when the promise of Love and Peace devolved into the strung-out weariness of Let it Be. Our goal is indeed to show how Birmingham had its own part to play in this story – far from the decade’s cultural epicentres, perhaps, but abuzz nonetheless with excitement and change. Would Yoko recall much now about a single afternoon over 50 years ago? Perhaps not. But, by placing our own stethoscope on this time in history, we are uncovering an art-scene as vibrantly experimental as Yoko herself was then, blowing bubbles in an Edgbaston suburb.

Edward Jackson. Thanks to the Midlands Arts Centre for archival materials, and to Dr Gerry Carlin for names and dates.

Written in contribution to Birmingham 68, an ongoing research project into the culturally significant changes and events happening in the city around 1968. Supported by the Heritage Lottery Fund, the project has enlisted the help of a dedicated group of local historians to produce a series of blog posts, podcasts and a final publication due to be released in early 2019.