Bob Linney Remembered

Just before the festival we were very sad to hear the news of Bob Linney’s passing. A restlessly inventive and thoughtful graphic designer, his career encompassed eye-catching jazz posters, banners for Greenpeace and Extinction Rebellion, cover art for The Beloved and UB40 and a series of workshops and collaborations in countries including Nepal, India, Mexico and Brazil.

When Bob visited Flatpack in 2018, it was to revisit his formative years at the Birmingham Arts Lab in Newtown. Here is an edited version of the conversation which Bob took part in at the Mockingbird with fellow poster wizard Ernie Hudson.

Bob Linney (BL): I got to the Arts Lab in the winter of 1972. The guy I used to work with was Ken Meharg - we'd both been to the university in Edgbaston and Ken started to print some student election posters and posters for music gigs at the Students Union - with help from another friend, Bob Blizard. When I finished doing my degree, I wanted to get the hell out of Birmingham and back to nature. So I moved up to the highlands of Scotland, with the idea that I would make a little screenprinting business doing the same sort of posters as we'd been doing down here. It became clear that there weren't really any events in the highlands that needed this kind of poster. So I came back, by which time Ken was at the Arts Lab. That was the end of 1972.

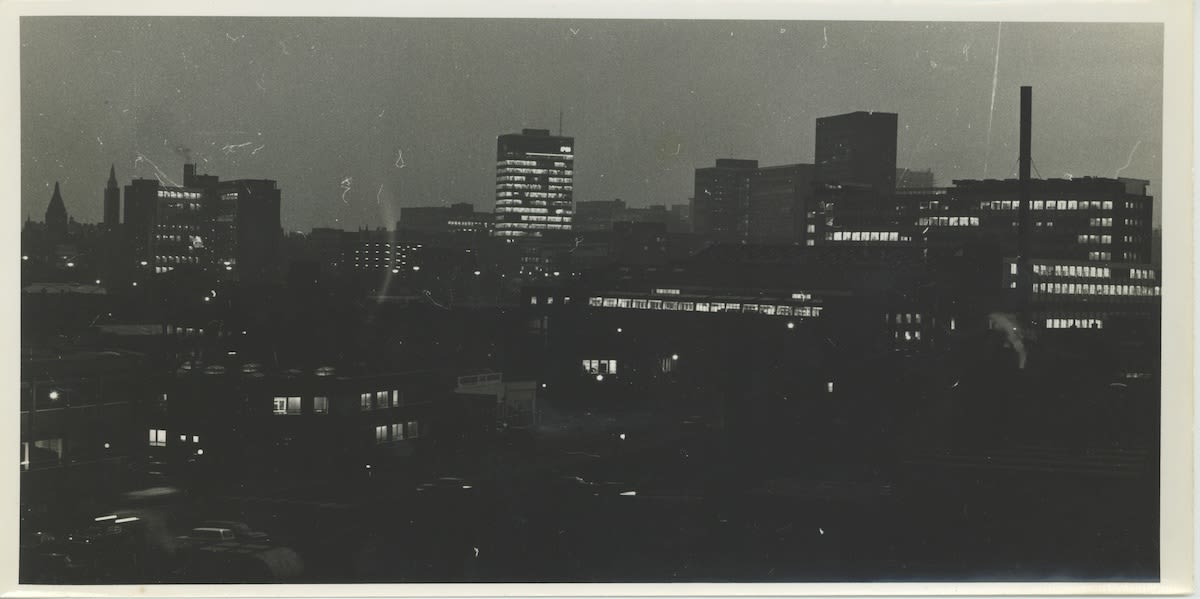

Ian Francis (IF): Maybe it would be worth just setting the scene a little bit as to what Birmingham was like in the late 60s, early 70s?

BL: There was a lot of concrete. I'd come from a very rural background, and I sort of wanted to get away from the city, really. I mean, there's nothing wrong with Birmingham, but everywhere you looked there were roads and underpasses and skyscrapers and things like that.

IF: It seems like the Lab became a bit of a refuge for people from this sort of nightmare that Birmingham was inflicting on itself, with all the concrete and the underpasses and everything.

BL: I guess so yeah. It certainly was a refuge from the sort of regular life.

IF: So it was a living, you said that there was more demand in terms of posters?

BL: One of the main things about the Arts Lab was the amazing film programme run by Tony Jones and Pete Walsh. It was said at the time to be the best arts film programming outside London. It was probably better than most of them in London. But a lot of the posters that we did were to advertise films that were going to be showing at the Arts Lab cinema, and yeah, there was a living of sorts. We managed to kind of crash out in various parts of the building at times, so we didn't have to pay rent, and they let us have a studio. The deal was that we produced the posters and got paid a little bit for doing so. I can remember the figure of eight pounds being what we were paid for 50 three- or four-colour posters, which doesn't sound very much but at that time it enabled me to go up to Liverpool, see my girlfriend, pay for train fare, and then I'd come back and do the next poster and repeat the process.

IF: But it wasn't a 9 to 5 existence. Work and play bled into each other quite a lot.

Ernie Hudson (EH): It wasn't really work. It was remarkable because everybody who was there wanted to be there. It was the first time I'd experienced that. There was nobody there for the money because there wasn't any. We got paid but it wasn't much at all. But there was complete freedom.

IF: I'm gonna show you a poster. Do you want to tell us a little bit about this Bob, Who's this? Is this a Ken or one of yours?

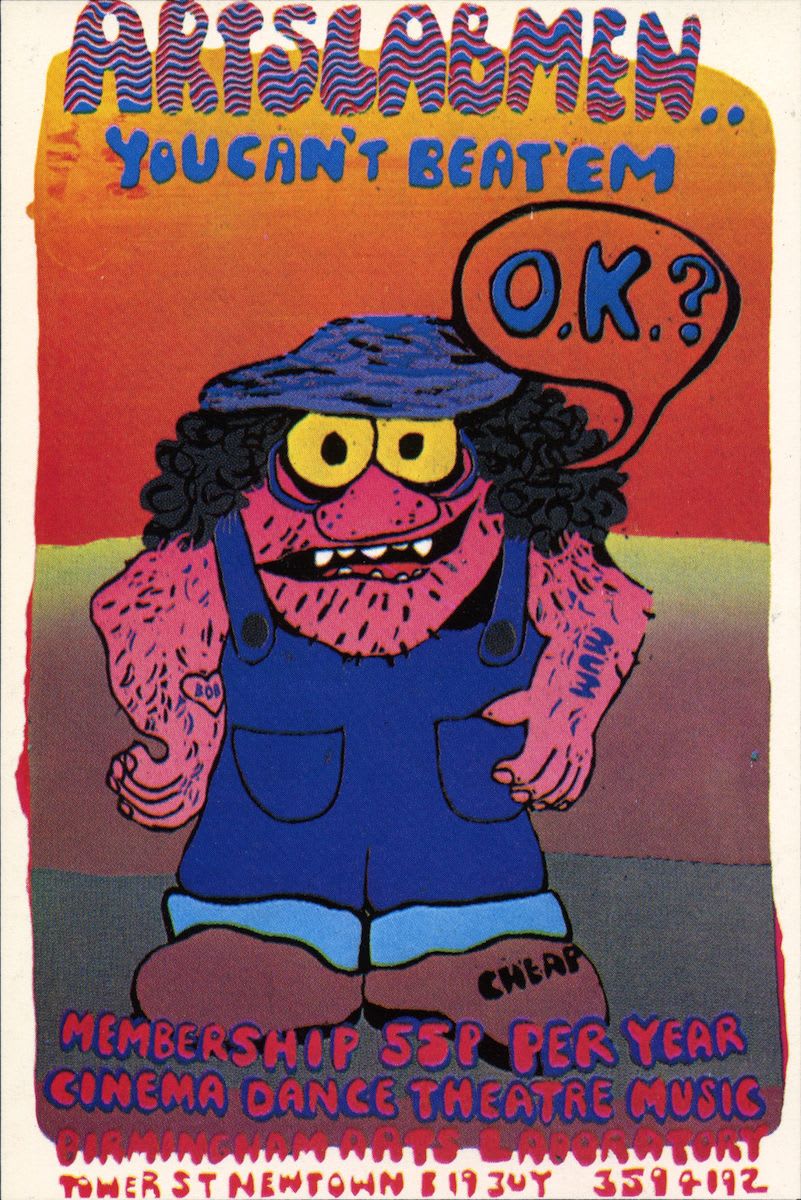

BL: It's more Ken than me. We often used to work very closely together on the same job. This one - there was a big advertising campaign at the time for Ansells beer, and the slogan was Ansells bitter men. I think it was Ken who thought it would be a good idea to do an Arts Lab men equivalent poster. So this is what he came up with. But when I when I saw it again a few days back, it made me think about the gender balance in the organisation. There were a few women involved, but mainly it was a boys club. Although there were there were lots of people of all sexes that came with various theatre companies and dance groups. One thing that really struck me looking back at that was how active it was. There was always lots going on, and new people coming in who would be doing some wacky kind of performance somewhere. So the boys club core was kind of diluted by people, sometimes women, coming in from the outside.

IF: Can you just say a bit about the process of building the silkscreen setup, because as with a lot of Lab stuff, it was essentially scavenging materials from where you could find them, wasn't it?

BL: Yes, the actual screen printing equipment we used to print the things, we made ourselves - it was all handmade stuff. At one point we needed to enlarge the dark room in the Arts Lab, so the first port of call was any skip in nearby streets. We got quite a lot of pieces of wood and stuff to first of all build the room, and then we had to equip it with graphic arts, photographic equipment, cameras and enlargers and that kind of thing. We went around to various auctions and bought equipment that other people didn't want, including at one point a big box camera on rails, you know that you kind of wound this thing back and forwards. You'd have sheets of film the same size as the posters, usually about 20 by 30 inches. For that, you had to develop the film in a developer, then put it in a fixer, then wash it all and hang it up. And that's one of the many things you can do now by pressing a button on a computer. Yeah, so it was improvised shall we say.

IF: And that improvisation led to all kinds of effects that you wouldn't normally get.

BL: Yeah, we did develop a technique that not many other people were using, and that was to use basically a water-based glue, which is coloured blue, which went by the grandiose name of blue filler. You'd paint this on the screen, and it would prevent ink going through. So you could make a stencil by painting this glue onto the screen. And then you printed through that and of course it cost next to nothing.

IF: A lot of the posters are for programming at the Lab - can you describe how it worked: they'd come to you with an event or a season that needed plugging? I guess you had a fairly free rein?

EH: There was complete artistic freedom. The cinema people would just drop the copy in - apart from Peter Walsh, he was always incredibly late with his copy. We'd be tearing our hair out waiting for the copy to come down. And we're going, come on Pete, we need 200 words. But of course he'd come down with a 1500 word essay - a textbook on contemporary cinema. And we'd just have to butcher it, and cut it down. But he never complained. I think he was so taken with cinema that he just couldn't help himself. He just had to write that much about any movie he happened to be discussing.

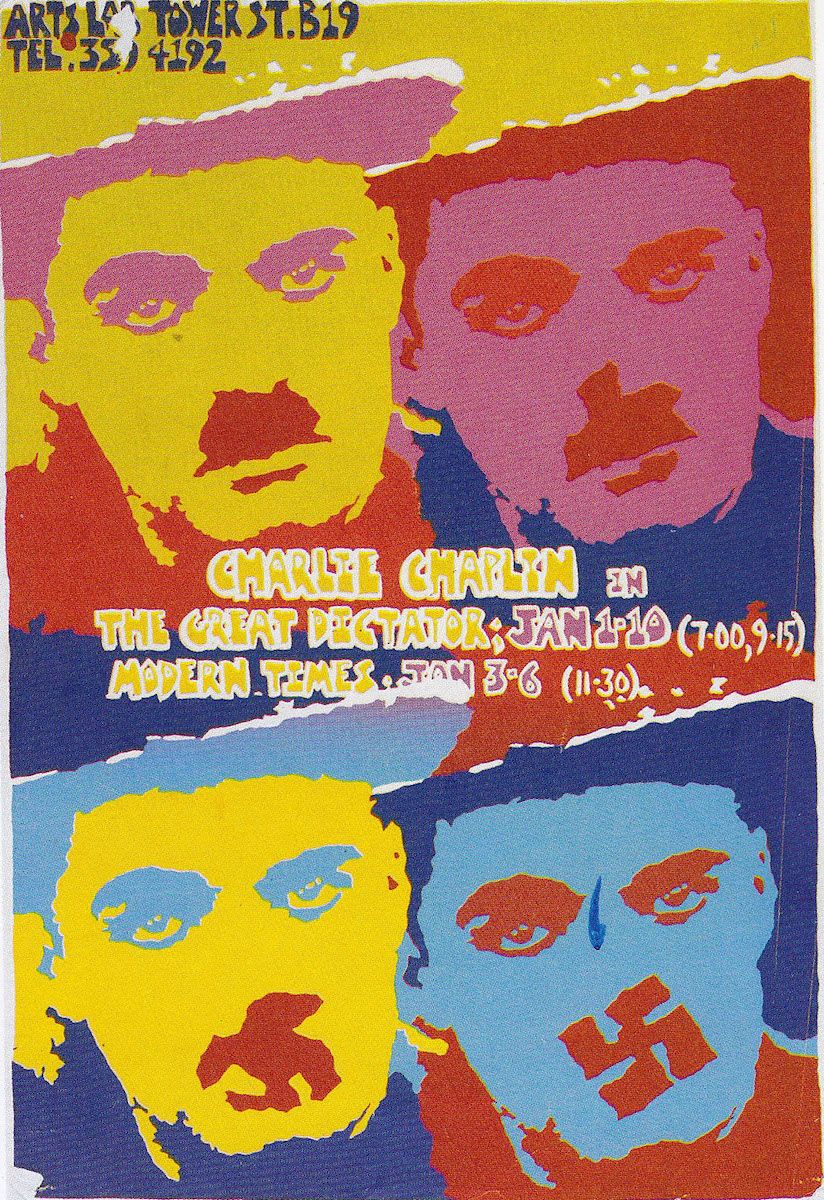

IF: With the posters you were making use of stills - you've got Chaplin here.

EH: I remember that one. I remember you doing that one, and the moustache emerging as you made it.

BL: Yeah, that's good if you read it in the right direction. This is something I touched on in later work overseas. Not everybody knows really to start at the top left, go to the right then back down here and across - some people might read it in a completely different way. In a sort of anti clockwise way or something.

IF: Do you think it actually helped in promotional terms? I always pictured these posters like plastered in underpasses and student venues - when you're talking about what how grey Birmingham was in the early 70s, it must have really stood out.

EH: Well they gave the Arts Lab a house style, definitely. And they stood out for lots of different reasons - use of handlettering, especially some of the later, looser ones - 10 years on, mainstream advertising was using that kind of lettering.

BL: Yeah, and one of the reasons we used very strong color was to try and attract people's attention to something that was maybe flyposted on a wall somewhere. Screenprinting, in particular, the printing process is such that it leaves a relatively thick layer of ink on paper. And the inks we were using were very strong, very intense inks. They were spirit-based, not water-based. People now tend to do screenprinting using water-based inks, which is a good idea because the fumes that came off the spirit-based inks were pretty horrendous.

EH: You could get pissed on half a pint after a couple of hours of that.

IF: Did it have an effect long term, being being exposed to ink that much?

BL: I think the Buddhists would say that it had some effect.

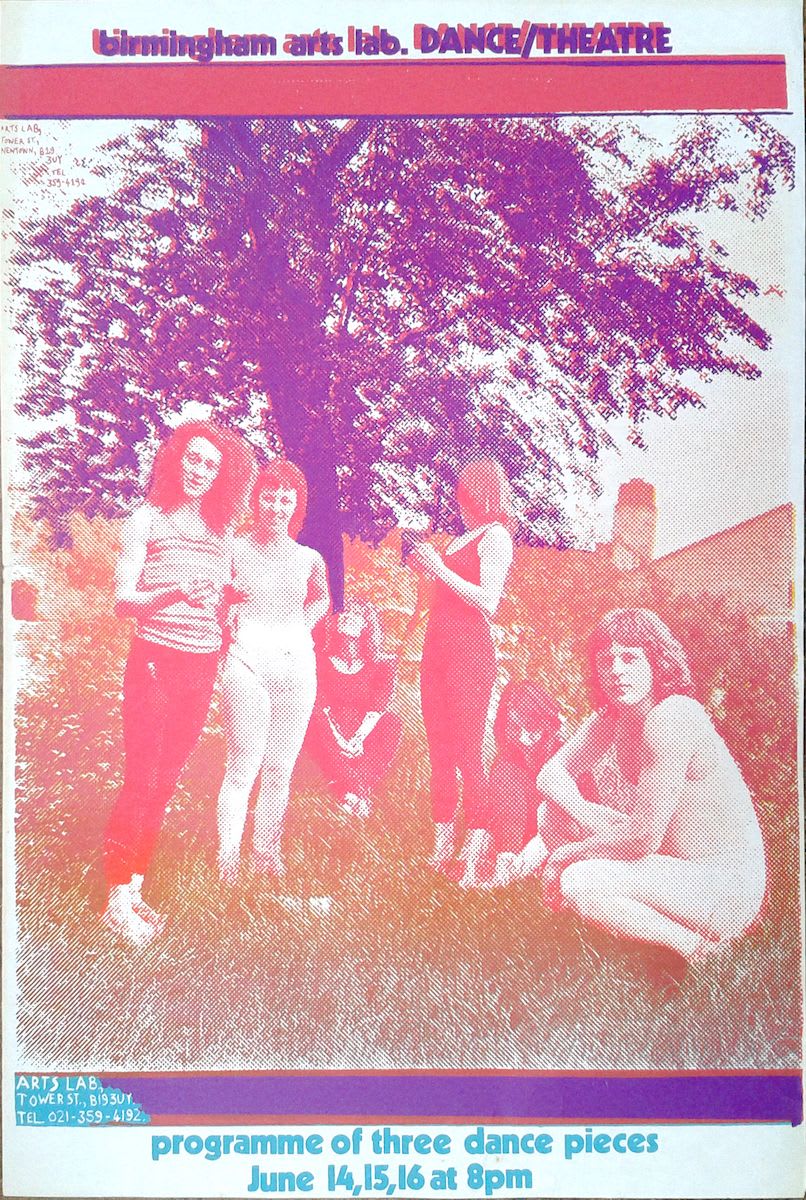

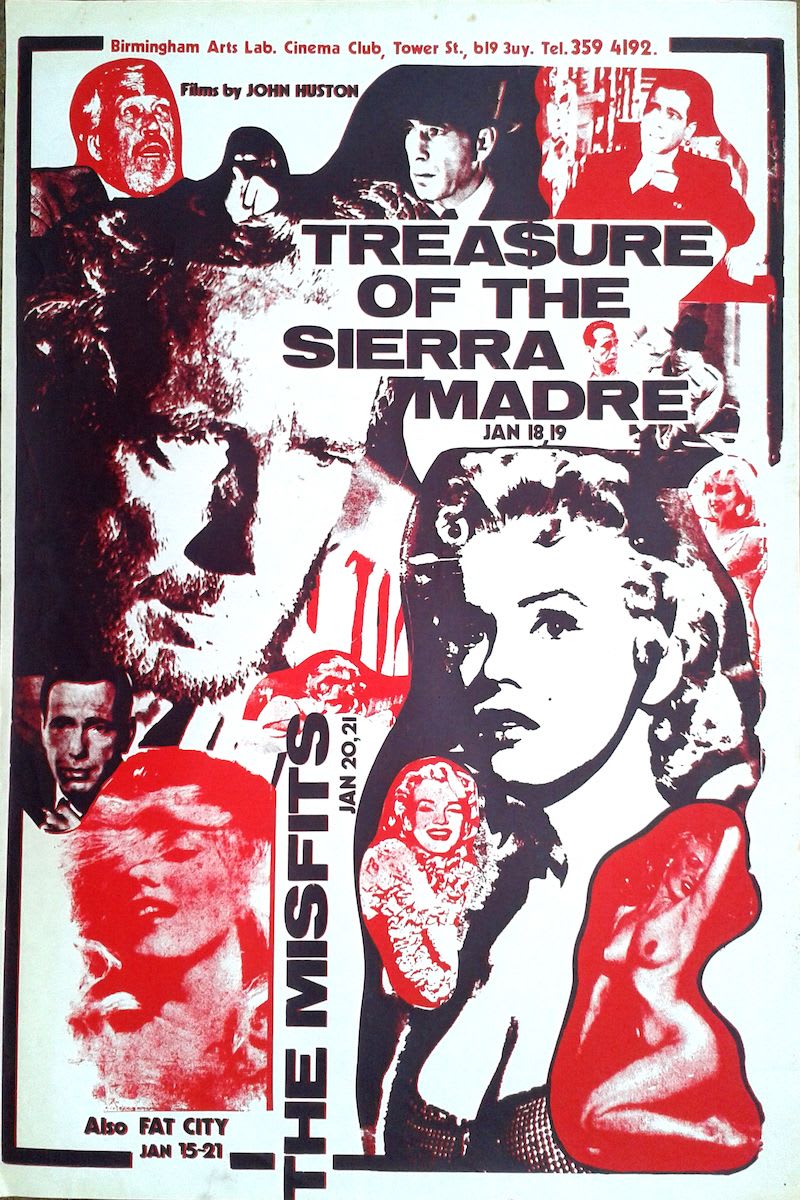

IF: This one here - we shouldn't under emphasise the role of sex in selling the Arts Lab programme - Tony and Pete were quite clever at programming saucy films, and you're kind of giving the impression here that you might see something saucy even though with The Misfits you're not.

EH: There were times when Tony used to stand watching the queue, looking out for the dirty mac brigade just to see if what he predicted was actually in the queue, and he was usually right. He knew exactly what he was doing.

IF: I mean, obviously it was it was an art cinema, but you would include Warhol or a bit of European cinema that would attract as you say the dirty mac crowd - that was partly what kept the place going.

EH: Well he did programme films that he knew could fill a house, just so he could also put on less popular material.

BL: Ken and I were always a little bit scared of Tony. He was sort of the adult really, while we were downstairs working away, splashing ink around and smoking dope. 'Oh, Tony's coming!' We were like little kids. But don't tell him I said that. He was very good to work for. In fact, this particular poster has got a couple of images of Marilyn Monroe with no clothes on. I can remember that I had to do it in a real big hurry. And in fact, that's a point generally about the stuff we did then, a lot of it was done really fast - there'd be very little notice sometimes. Not for any reason, but because they didn't know if they were getting the film or not. I remember him giving me a sheaf of black and white photographs, and I had to do the poster the next day. So I just sort of collaged most of what he'd given me without thinking too much about, you know, what people would say about it 40 years later.

IF: But you didn't think of it just as throwaway publicity, did you?

BL: That's quite an interesting area. Because later on, we were sort of taken up by the British Council. And they put on two exhibitions, each of which had about 60 posters in them. The idea was that they represented something of alternative British culture in the 1970s. These exhibitions would be sort of big galleries and people who are responding to them as if they were fine art, which they they weren't, you know, they were just things that we did at the Arts Lab. We never really imagined that they'd have a life beyond a couple of weeks of being fly posted somewhere. And then to see them all in frames, and the British ambassadors coming up to congratulate you, 'what a beautiful piece' - you know, you think 'what the fuck's this all about?'

IF: Ernie, you paint now, how do you see the connection between the stuff you did then and the stuff you're doing now?

EH: Well, it's colour really. To me, when I used to open a five-litre pot of ink, it was almost like you could lick it. And the process itself, you do all this preparation, fanny about for hours and hours to get it just right. And then you pull the squeegee across them, and it has this big swathe of colour. And the next one, you did a bit more dicking around, then threw another color on. Using the blends, you've put a blend on and then the next one you put on, you'd get six or seven colors in the next one. Multiply it really quickly. There are those that say silkscreen is too seductive. You know, art college lecturers.

IF: Because it looks too nice. That is a thing in conceptual art. It's not about looking pretty. It's all about the idea. You were freed up in a way by the fact that it was just publicity. You didn't have to overthink it too much.

EH: You couldn't ovethink it because it had to be out the next day - they always wanted it yesterday.

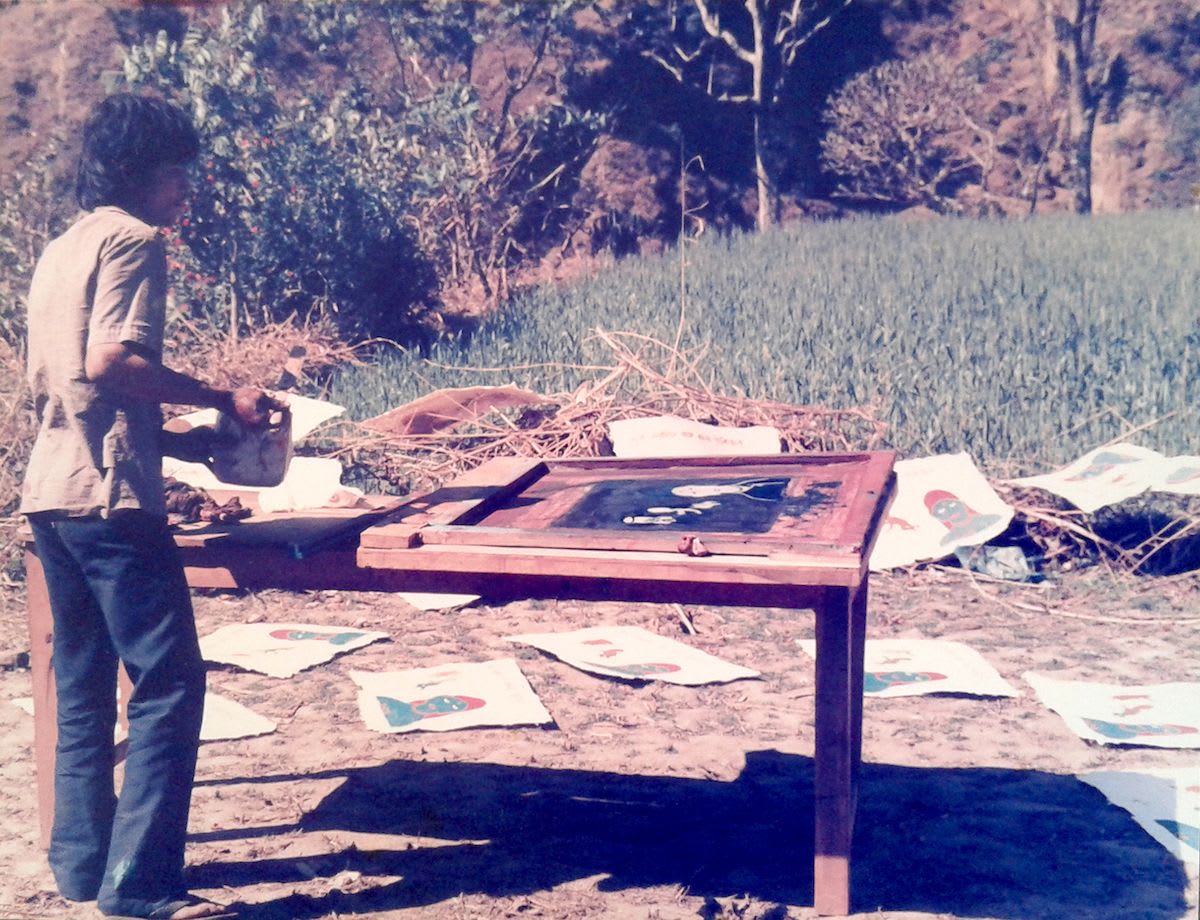

IF: I just want to show a bit of post-Lab work by Bob. Tell us about Nepal, what's happening here?

BL: Well, that is somebody screenprinting in the open air with the simplest equipment you could imagine. We were working in a village in Nepal with UNICEF, and we did experiment with trying to make the blue filler locally appropriate. So they suggested that we boiled up some shin bones of water buffalo, in order to make some glue. We did a lot of work in all different parts of India and in Nepal, and loads of other countries. It was a very educational time for me, we were trying to develop images that people could understand. And a lot of the people who would be seeing those image had never seen any picture in their lives before. It made me go back to thinking how pictures are constructed. There's 101 pictorial conventions that we all in this society learn without realising we're learning it.

IF: So moving into the 80s and 90s, you've done a lot more with charities and NGOs, and music work as well. The techniques are very different, obviously, you're not screenprinting anymore. You're working on the computer.

BL: Yeah, I mean, for 20 or 25 years half my time has been taken going off to anywhere: African countries, Brazil, Mexico, India, all over doing training workshops for people like community health workers, who could use imagery or simple images, to communicate with people in in their own community to try and improve health status for example. So, half of my time was spent doing that, usually either in urban slums or in refugee camps or in rural areas sometimes. The other half I was still continuing my graphics work here, which included a lot of music posters, album covers, CD covers.

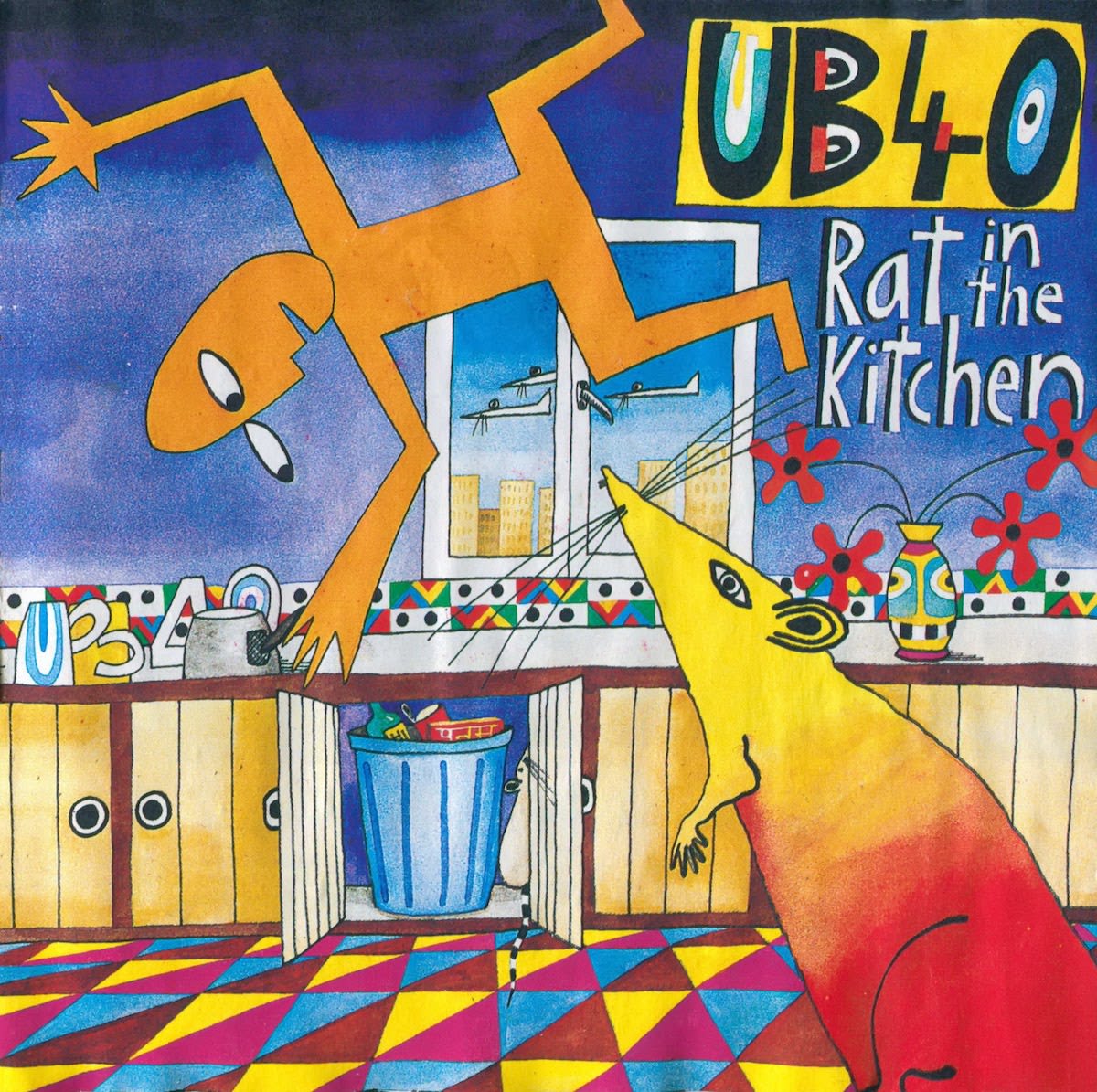

IF: And on a Birmingham note you also did UB40 for a while.

BL: That's actually a picture of our kitchen. There were planes flying in the background. I live in Suffolk and they used to have American air bases there. We used to get these planes coming over, really noisy. People used to throw themselves under the kitchen tables. So those airplanes are a reference to that - they're F1-11s. Legally the British planes were not supposed to fly below 350 feet, but the Americans could fly down to 250 feet - so it’s the idea of us being an aircraft carrier for the Americans.

IF: Did you know the Campbells already from your time in Birmingham before, is that how you ended up working on UB40 stuff?

BL: No the UB40 stuff, the guy phoned me up one night at about half past one in the morning. I was asleep. Phoned me up: 'Ah, Hi, I'm the manager of UB40 over here in California. We'd like you to do this. How would $2,500 be?' I said 'fine, I'll go back to sleep now.' That's how it happened. He'd seen some stuff.

IF: Did you find that you were getting work off the back of the Lab posters - even though it didn't make much at the time it was a useful thing to show?

BL: Yeah, I suppose. Yeah.

EH: Well, we're here over 40 years later talking about it which is astonishing really - if you think about how they were done.

BL: Yeah well, everything is strange when you've lived so long.

IF: So how do you feel when you see your work being picked up like this and still enjoyed by people. How do you reflect on that time when you look back on it now?

EH: Well, they were great times. I mean, we met over a nice Lebanese spliff in the back of the Lab. It was all very relaxed.

BL: Yeah, it was. Now there are art centres in every small town or village in the country, and they're all run by retired people, old farts who haven't been involved in the arts all their lives. And they can be terribly conservative and staid. But the Arts Lab really wasn't like that. It was a product of the time because we did seem to be able to do a lot of things without having a great deal of funding. I agree with Ernie, it was good fun. Ernie and I used to be very interested in sound. So we'd go out onto the roof of the Arts Lab - as long as Tony wasn't anywhere around. We used to get some nice Nepalese black up on the roof there, and listen to the cosmic roar of Birmingham.

Additional links:

- Guardian obituary

- 2020 podcast in which Bob discusses his work with the Beloved

- boblinneyposters.com

- 2009 interview with Pete Walsh

Image of Bob Linney at Flatpack 2018 courtesy of Bob Blizard.