Black and White Unite and Fight

The last of our Birmingham 68 book extracts comes at a sadly appropriate time, given the events of the past few days. It's the story of a half-forgotten anti-racism rally which took place in the city centre a couple of weeks after Enoch Powell's 'Rivers of Blood' speech, and the aggressive police response which it provoked.

It's a crisp, warm Sunday afternoon in central Birmingham. Demonstrators are filing into Victoria Square in anticipation of a visit from Prime Minister Harold Wilson, due to give a speech in the Town Hall at 3pm. There's an eclectic array of placards on display: students in donkey-jackets proclaim 'Yankee Aggressors Out of Vietnam' and 'Wilson is an Optical Illusion'; smarter and more orderly, a large group of Indian and Pakistani workers carry signs reading 'Black and White Unite and Fight' and 'Prosecute Fascist Powell'; bringing up the rear, a group of dancing, singing African protestors attack the 'Nigerian genocide' in Biafra. There's a large crowd of curious onlookers, from school-kids to old ladies, and on Galloways Corner at the top of the square a pocket of fascists is chanting "Send 'em back!" Among them is Colin Jordan, a former Coventry school teacher and prominent British nationalist.

On Wilson's arrival the atmosphere audibly changes. We see him escorted between the Town Hall and Council House to a chorus of booing and shouting, while a police cordon attempts to hold back demonstrators. There are flare-ups between the different factions. A police line stands between students and Asian workers on one side and Powell supporters on the other. An older man with a Brummie accent is getting increasingly agitated and gestures towards the Council House: "You've got Wilson behind you, a black-lover. If Powell was Prime Minister... he'd bin the lot of you." One student protestor says to the police "aren't you going to help us?" In the wake of Wilson's departure things begin to fragment. Some protestors are led away. Another placard: 'Would You Let Enoch Powell Marry Your Daughter?' Jordan is hoisted up on the shoulders of some of his supporters, amidst tentative Nazi salutes. A big group of Asian workers is dispersed (some would say shoved) down the hill towards Pinfold Street by the police.

This footage came to light during our Birmingham 68 research, unseen since it was filmed by an ATV news cameraman on 5 May, 1968. It's about 16 minutes worth of rushes from the 'Black and White Unite and Fight' demo, which had been organised by the Indian Workers Association in response both to Wilson's visit and also to Enoch Powell's speech at the Midland Hotel a couple of weeks previously. Although Wilson defined himself against Powell that day, his own Labour administration had been in power for four years and their record on race relations was seen as distinctly patchy. Having in opposition decried the Tories' Commonwealth Immigration Act, designed to limit the number of people arriving from Britain's former colonies, in early 1968 Wilson’s government actually strengthened the Act with the ‘grandparent rule’, in response to fears of an influx of Kenyan Asians. There was a clear sense within both of the main parties that standing up for the rights of immigrants was not a vote-winner, also reflected on a local level. In Second City Politics Kenneth Newton detailed the levels of ignorance and bigotry among Birmingham councillors at this time, and concluded: "Race relations in Birmingham has been half a political issue because only half the case has been put - the case of coloured immigrants has yet to see the light of day as a force in local affairs."

One of those attempting to address this vacuum in the late sixties was Avtar Singh Jouhl, an organiser of the 5 May march. He had arrived in Smethwick ten years previously from a farming background in Djalandar. Like many others he had grown up on rosy images of the UK and was dismayed by the smog and poor conditions he encountered. Having already been involved in student politics in the Punjab he soon joined the Indian Workers Association, a UK-based leftwing organisation which had formed in the 1930s to support India’s fight for independence. By the late 1950s their focus was on tackling the discrimination faced by migrant workers, from lobbying for equal pay to protesting the widespread colour bar which could be found among pubs, shops and rental accommodation at the time. At one point Jouhl, by then the group’s national general secretary, was arrested and later cleared after refusing to leave a Black Country pub on the grounds of his skin colour.

The 1964 election established Smethwick as a symbolic battleground in this fight. Bucking the national trend, local Conservative candidate Peter Griffiths unseated Labour MP Patrick Gordon Walker with the help of some inflammatory anti-immigration rhetoric later attributed to Colin Jordan and fellow nationalists. Having been closely involved in the counter-campaign, the IWA then managed to secure the visit of Malcolm X a few months later, a PR coup which briefly put Smethwick in the media spotlight. The alliances with black activists and student groups which Jouhl and his comrades forged at this time would prove vital when they were planning the Wilson rally in 1968.

On the day of the protest Jouhl came straight from his brother-in-law's wedding. The police were keen to keep marchers away from Town Hall, and sent them on a route around the city centre while Wilson was speaking. Some returned to the square once the march had ended, and as the ATV footage shows they received far more attention from the police than the fascists did. Shortly after the cameras stopped rolling things became more heated on Pinfold Street and IWA leaders Jagmohan Joshi and Sohan Singh Sandhu were arrested and bundled into a van. In Jouhl's account: "I was appealing to the demonstrators in Punjabi - 'dont worry, we will get them bailed out' - and when I was making this announcement two policemen arrested me. They didn't know what I was saying and thought I was inciting the demonstration against the police." Jouhl joined his comrades at Steelhouse Lane police station, and the following day was charged with disorderly conduct. The Stipendiary dismissed the charge: "The accused seems to have taken a responsible view of his duties as the organiser of a demonstration. It is not impossible that he became excited, and there may have been some misunderstanding as he was talking in a foreign tongue."

Also in court was Frederick Haywood of Handsworth, who on being fined £5 for a disorderly act responded: "The way I see it, fighting Fascism should be commended not penalised." In total ten were arrested at the protest, including a couple of IWA members who had to be treated in hospital for injuries which they alleged had been caused by the arresting officers. Joshi attempted to bring a case of police brutality, describing the course of events in a letter to the Home Office. In a reply David Ennals wrote that there was no case to answer, and that "the Chief Constable of Birmingham is satisfied that the police acted with admirable restraint and tolerance throughout." When Jouhl attempted to organise a similar protest the following summer, he remembers being advised by the Superintendent: "be very careful Mr Jouhl - last time you got off, but next time we will make sure you don't."

"We do not sit back, we hit back" is a phrase that recurs in IWA literature and speeches of the time, reflecting the influence of Malcolm X and subsequent black activism, particularly in the wake of Martin Luther King's assassination. The association was increasingly disillusioned with a legislative and lobbying approach which seemed to have brought limited progress, and in the wake of Powell's speech there was a renewed appetite among black and Asian groups to make common cause. On 29 April over 50 organisations including the IWA signed a Declaration of Black Unity at a house in Leamington, the same house which had a burning cross nailed to its door by a short-lived attempt at a Ku Klux Klan chapter in 1966.

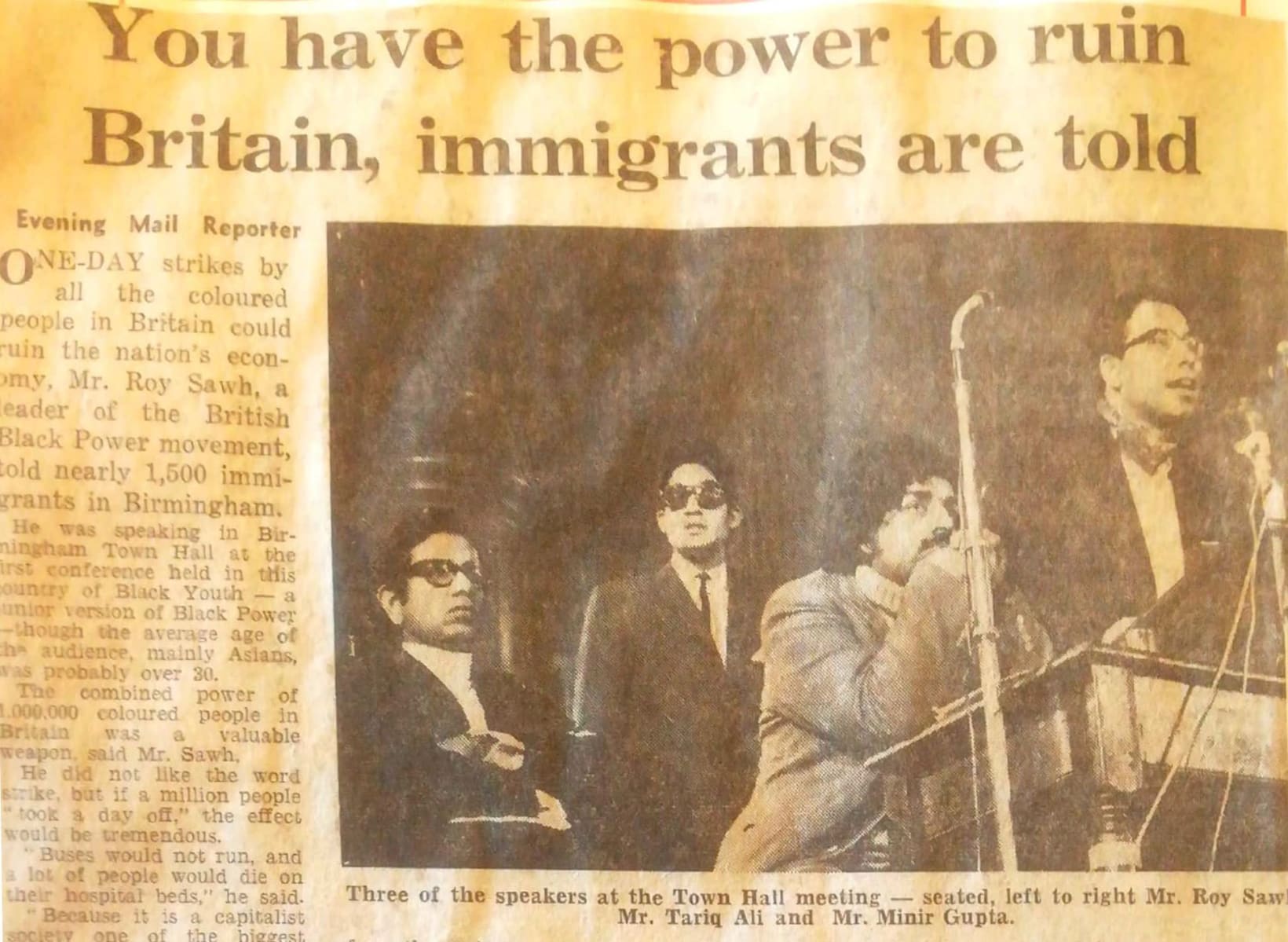

By the end of the year an audience of over a thousand - predominantly Asian men - gathered at Town Hall for a Black Youth conference organised by Mihir Gupta and featuring Tariq Ali. On the podium Gupta advised: "If a white man slaps you, slap back... The days of turning the other cheek are over." Gerry Archer of the West Indian People's Union remembered the Birmingham that he arrived in during the early 1950s as "a broken-down, bomb-damaged shambles of a city... Today we have the second most modern city in the country. Whose labour built this? Ours. What do we hear from the racialist Birmingham City Council? 'We will put up check-points at the entrance to see that no more immigrants arrive in the city.' That is a good thank you for what we have done for them!"

The alliance struggled to sustain itself for long, unable to contain a diversity of moderate and radical voices, but this period marked a step away from the rhetoric of assimilation towards an emphasis on plurality and equal rights. Reflecting back fifty years, Avtar Singh Jouhl saw it as "an important chapter in the struggle... for the generations born afterwards, they didn't experience the cruel type of discrimination we experienced during the 50s and 60s." However, speaking a few days after Boris Johnson had likened Muslim women to 'bank-robbers' and 'letter-boxes', he was also confident that some things do not change: "At every stage, you've got no alternative but to fight. Unless you fight back they will win, like the Nazis won in Germany." Along with others we spoke to, Jouhl felt that narratives of 1968 had been skewed by a preoccupation with 'Rivers of Blood'. "Enoch Powell's speech remains up on the wall for people to remember. Many incidents or events are not up on the wall."

Lead images taken by Nick Hedges on 5 May 1968. Text from This Way to the Revolution, our book on late 60s Birmingham.