Billy Willy Interview

Directors Sean Mullan and Michael Barwise look back on the making of their documentary Billy Willy, the story of a friendship in a city scarred by its past.

There's a duo behind and in front of the camera: how did you two meet? Had you worked together before?

[Michael] - This is actually the first time we made a film together. Prior to this we met through the local Derry film scene, and both shared an interest in what kind of films we liked and what kind of work we wanted to make.

[Sean] - So we always wanted to work together. Billy Willy began as a catalyst project to get the wheels turning on collaborating, and as we worked on it, it really took on a life of its own.

And how did you meet these larger-than-life characters that are Billy and his friend Willy?

[Sean] - Willy is actually my cousin who has been coming for dinner to my family home for the last 15 years. Over this time, I heard of Willy telling us how he met a new friend. Anytime he spoke about him he was upbeat and buzzing about it. One day he asked could he invite his friend for dinner, (meanwhile Billy was already outside waiting on the pending decision!). Of course, we said yes and in walked Billy. As we had dinner, Willy told us about how Billy introduced him to jazz and over years that dinner and their friendship stuck with me. Then in 2018 at the Derry Jazz fest, I decided to revisit that memory and go out filming with them.

The film mixes interviews, archive, animation... How did you put these elements together?

[Michael] - We started with a bunch of material Sean had shot over a year with Billy and Willy. This was footage of Billy and Willy at the Derry jazz festival and performances in the front room at Christmas. So the starting point was always their friendship and music.

[Sean] - Yeah, in particular it was the friendship on the periphery of society. Billy and Willy were always well known about town and welcomed in, yet they seemed to always be on a different quest. I would go for lunch and walks with them and they would tell me short stories and show me places they like to visit together.

[Michael] - In our general discussions we’d been chatting about memory and identity and then we came across the footage of Billy singing in the 1970s BBC documentary ‘Children in Crossfire’. Combining this with what Sean had already shot and our shared interest in similar areas, it opened the door into interweaving Billy and Willy’s friendship into a larger narrative. The mix of mediums came organically in the edit in reaction to the story’s altered states of consciousness.

The film contains several references to the Jungle Book, through the animation and the voice over. Where did these ideas come from?

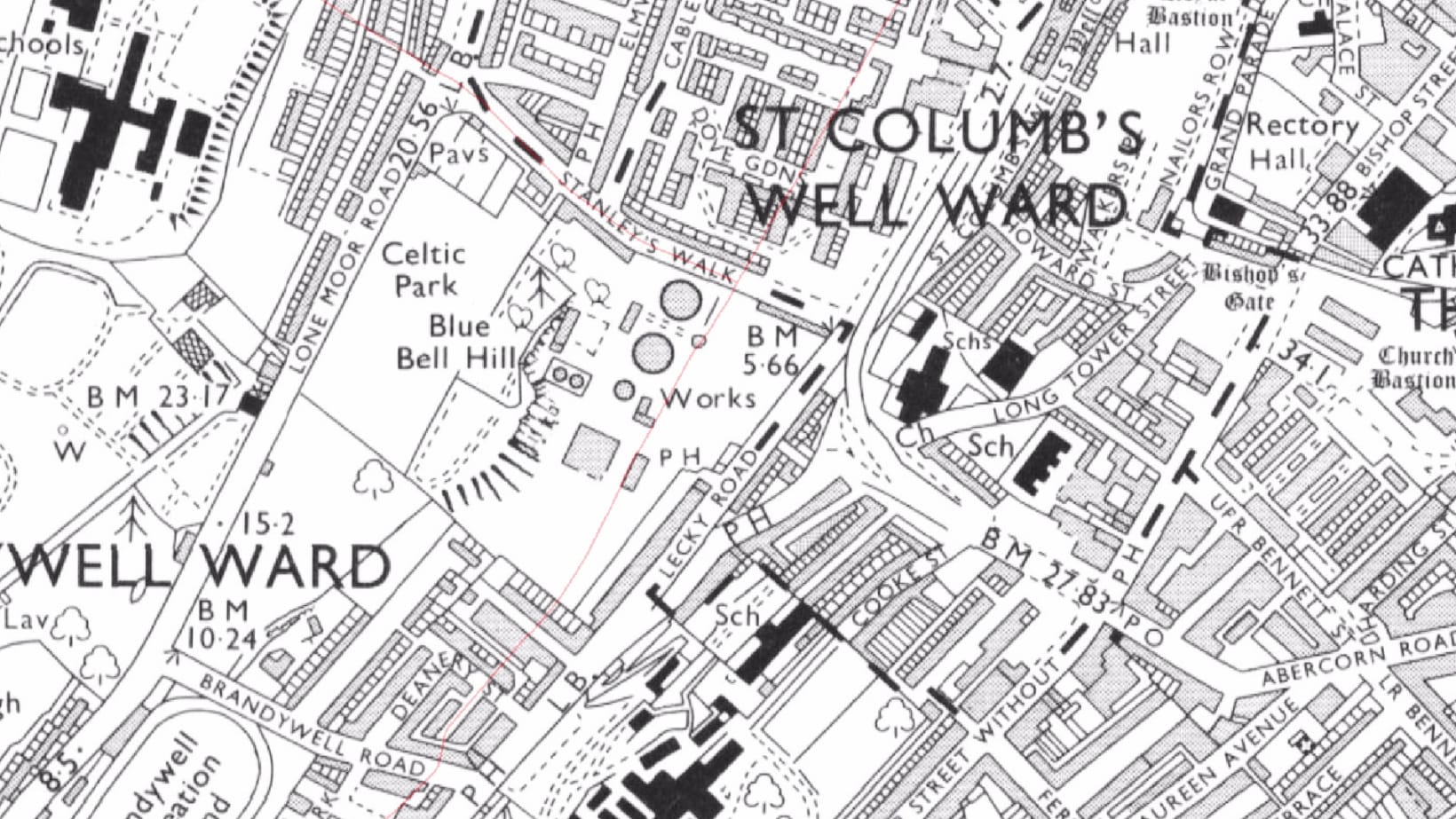

[Sean] - Billy once performed ‘I wanna be like you’ and told me it was his favourite song. He said he listened to it all the time when he was younger and had decorated his entire bedroom in honour of King Louie. I found a certain poignancy in his passion for the song and the lyrics of ‘I wanna be like you’. Billy has a great memory for recalling street names and routes around town that are no longer there due to reconstruction of certain areas he grew up in during The Troubles in Northern Ireland. With myself and Michael’s research into time, place and memory we wanted to create a fictional tour guide based on Billy’s own version of his friend King Louie. In doing this, it allowed us to travel through both the physical past and the mental past of Billy’s mind.

Your documentary looks at both the geography and the history of the city of Derry, with archive, maps, and recurrent shots of the Lecky road flyover. What does this place stand for?

[Michael] - The connection to the Lecky Road came from the footage of Billy singing as a child in the BBC documentary. This was recorded outside his school there. The flyover was built during the 1970s and it cuts through the Bogside area in Derry. In order to build it, they had to demolish and completely reshape the streets and housing there. So in a way we were interested in physical and architectural scars, and how people and places change. And scars are always a story, bad or good. The flyover itself has always had a presence and a somethingness about it, in part I think that comes from it seeming so out of place amongst the architecture around it. There’s something otherworldly about it amongst the murals and history of the Bogside.

The editing is very musical, with echos and repetitions. What was your approach?

[Sean] - We had no budget for this project and produced it ourselves. Therefore we were given the freedom to enter the edit with alot of creative control but also forced to dig deeper into telling this story in a more inventive manner. We both agreed that we didn't want to make a voyeuristic piece of mental health and that Billy and Willy were very much involved. So taking this process into the edit we kept it open and reactionary to the spontaneity of their friendship and feelings.

[Michael] - The music allowed us to travel between worlds and states in a fluid way. We sort of embraced the approach of jazz too, in terms of finding rhythms between images that resonated without always having a completely logical reason for doing so. Always playing and forming different types of connections. Feeling was such a big part of the edit, because the motto was always “if it felt right then it was right” and that’s actually a really liberating way to work.

At the heart of the film is a beautiful friendship, but also a troubled past. There's a real ambivalence to your film, which is both sweet and heartbreaking (just like the last scene of young Billy and old Billy singing side by side)...

[Sean] - I think friendships are always quite ambivalent and enigmatic. You often never quite know why or what it is that made you become friends, when they started or for that matter ended. But we remember how we feel during these times, and it was this sense of intangible feeling of friendship through time that we wanted to catch.

Of course, friendships like this are a cog in a larger story for everyone during traumatic conflicts and happier times. Michael and I wanted to extend and explore the idea of observing a city’s physical and mental health altering over time. Can the landscape of a physical place show signs and leave behind the residue of a psychological history?

[Michael] - We’re interested in the idea of person and place being inseparable, as in not really being able to gain a full understanding of one without the other.